Anyway, on to the Battle of Leuktra, one of my favourite battlefield victories, where clever thinking and the Power of Love gave a wily Greek statesman an impossible victory over an invincible enemy.

The Spartan Way

As I said, this entry ended up being way bigger than I planned. The glory of the internet is that information has broken free of the universities; like Leonardo's sketchbooks, which are finally being reviewed by engineers and not just art historians, the basics of Greek warfare are now being analysed by experts in fields like psychology and crowd control. The result is a fractal effect, where every aspect of Greek warfare has come under as much deep analysis as the whole. As I did my research it was gratifying to find better minds had been there ahead of me, but at the same time I could feel myself falling down the rabbit hole.

Nevertheless, here's what we know: the vitality of the ancient Greeks was the result of the tension between two contradictory ideas. The Greeks occupied a landscape of small plains wedged between towering mountain ranges and wine-dark seas, making every city effectively an island, whether an island surrounded by water or an island surrounded by mountains. This made power projection a strictly local concern, and also turned the battlefield advantage away from archers and toward heavy infantry, so the core of any Greek army became a number of armed citizens called hoplites ("well-armed men"), who fought together in a phalanx. But the hoplite's arms and armour were expensive, costing roughly as much as a car, restricting phalanx duties to the middle-class and above, people who had a stake in the society they were defending and understandably wanted a say in how it was run. Thus the democratisation of the battlefield led to the democratisation of politics.

This promoted a very different society to those of the Fertile Crescent, where a god-king could marshal the resources of a vast, easily-travelled plain and reduce the common man to little more than a slave. Thus, although united by ethnicity and a common language in a phenomenon we'd now call Nationalism, the basic unit of classical Greek politics remained the city-state, or polis. The duality that folded within itself was that Greek independence forged a reverence for the individual that we still hold today, but could only be maintained while they submitted to the idea that the polis was more important than any individual.

A good hoplite in a phalanx is therefore not necessarily the one that kills the most of the enemy, but the one who "holds his ground," one that does not desert the battlefield, or more importantly his position in the line. It has been recorded in more than one ancient Greek battle of a warrior encountering bloodlust, a state in which the warrior goes almost crazy, leaving his position in the phalanx, going forward and starts to kill the enemy of his own accord. In these scenarios, after the battle, the warrior was then demoted, reprimanded and ridiculed in public. The heap of dead enemies he killed counted little compared to the fact that he gave up his position in the phalanx lineup.

No polis took this to a greater extreme than Sparta. Located in the extreme south of Greece, in the valley of Lakonia in the Peloponnese, the Spartans were a people

who looked at the question of Death or Glory and asked, "Why not both?" Lakonia was a small fertile plain surrounded by high mountains that provided access through a few easily-defended passes. Growing up here, you got the feeling that all you had to do was hold it, and this little Elysium could be yours. Sparta was the only polis in Greece to remain unwalled; when asked why, King Agesilaus pointed at his men and said, "These are Sparta's walls."

Hence, Sparta became a war machine and nothing else. The only career was the army, just like Virginia, and there was a long-standing tradition of slavery (again, like Virginia). These were the helots: squeamish historians call them "serfs," but don't you believe it. Every year they received a stipulated number of beatings regardless of any wrongdoing, and each autumn the Spartans actually declared war on them, just to put them in their place: citizens (meaning the hoplites themselves, called spartiates) received absolutely no punishment if they killed one. The Athenians next door weren't big on human rights, having a large, slave-based economy themselves, but even they never declared war on their slaves. The Spartans were different that way, seeing themselves as a small garrison over an uppity population of helots that had to be kept under the heel at all times, but the benefit of this system was they didn't have to provide their own upkeep. Thanks to a slave economy, the Spartan soldiers were free to spend every waking minute preparing for war.

Hence, Sparta became a war machine and nothing else. The only career was the army, just like Virginia, and there was a long-standing tradition of slavery (again, like Virginia). These were the helots: squeamish historians call them "serfs," but don't you believe it. Every year they received a stipulated number of beatings regardless of any wrongdoing, and each autumn the Spartans actually declared war on them, just to put them in their place: citizens (meaning the hoplites themselves, called spartiates) received absolutely no punishment if they killed one. The Athenians next door weren't big on human rights, having a large, slave-based economy themselves, but even they never declared war on their slaves. The Spartans were different that way, seeing themselves as a small garrison over an uppity population of helots that had to be kept under the heel at all times, but the benefit of this system was they didn't have to provide their own upkeep. Thanks to a slave economy, the Spartan soldiers were free to spend every waking minute preparing for war.

Helmets had moved on from the iconic full-face "Corinthian" variety to a more open "Chalcidian" design that left the face more exposed, but was also much less restrictive of vision and hearing. In a Corinthian helmet you could see straight ahead and nothing else, leaving you no view of what might be coming in from the flanks and, even worse, no view of the ground, making even the smallest rock a trip hazard.

The weapons were iron. Despite being the most common element on earth, iron wasn't yet very popular as it wasn't noticeably harder than bronze, but smelting it required much higher temperatures than a wood-burning fire could manage (1,500-1,600ºC, compared to the 600 or so for bronze). The manufacture of steel had already begun, but no blacksmith really understood that yet – any carbon introduced to their iron was usually incidental.

The primary weapon was a mid-sized spear about 2.5m long called the dory. The shaft was made of cornel, a wood so dense it actually sank in water, and at the business end was a beautiful, broad, leaf-shaped head made of a steel casing on a wrought iron core, crafted using the cementation process (i.e. melting both and iron together until they bonded while still in a liquid state). Beaten into shape and sharpened on a stone, the head was capable of going straight through an unarmoured man, cracking any ribs that got in the way and opening up a vast cavity to bleed him out. An episode of Deadliest Warrior tested the dory and the Wiki dutifully recorded:

The dory spear was first tested on a dummy while its thrusting force was measured and it was theorized that the measured force of the thrust was equivalent to a two-storey fall onto the same spear if it were to be held up vertically. The dory was next thrust at a gel torso where it proved to be a devastating blow, causing a laceration, breaking ribs, piercing the heart and a lung, and exiting the back.Not quite an accurate test in my view, as the tester used an underhand stroke rather than a weaker overhand blow (more about which later), and to my frustration, they never tried it on an armoured dummy. But still, a hell of a weapon. Given the softness of bronze and the heft of the iron head, I would guess the dory would be capable of punching through a thorax, but it would take a really hard thrust, and you'd have to get the angle just right (a deflection would be more likely than stopping it cold). At the other end was a bronze point called the sauroter ("lizard-sticker"), which could be used as a backup spearhead if the main point broke off, or just to brace the spear in the ground (its bronze construction helped keep it from rusting).

Despite its sturdy construction the dory often broke, so the Spartans also carried one of two sword designs, the xiphos or kopis. The xiphos, a beautiful leaf-shaped blade common throughout Greece, was made even shorter in Sparta to make it usable in the crush of colliding phalanxes (only 300-450mm compared to the average Greek's 600mm. In one account an Athenian asked why a Spartan's sword was so short, to which the Spartan replied that it only had to be long enough to reach the Athenian's heart). The kopis by contrast was a weighty, dog-legged blade that kinked forward halfway down. As a slashing weapon only I have doubts about its usefulness in a phalanx, where there would've been precious little room to swing it and no chance of hacking through armour – but as we'll see, the actual physics of killing are the least important aspect of a weapon. It would've been brilliant for swatting away incoming spears, where the more breakable xiphos would've been useless, and it just looked mean, which shouldn't be discounted. Neither was even remotely similar to the oversized piece of shit Gerard Butler carried in 300.

The defining feature of the hoplite however was his huge, heavy shield, the hoplon ("piece of equipment"), which the Greeks called an aspis. It measured almost a metre in diameter, weighed

about 7.5kg, and was usually 25-40 mm

thick. Most of this thickness was the wooden core, but the aspis usually had a bronze skin front and back, and some had a layer of leather as well. It was without doubt one of the most advanced pieces of military tech in the world: the wooden core gave it fantastic energy absorption, while the bronze exterior shrugged off sharp points without letting them dig in. Most important was the grip, known as the Argive grip, whereby the hoplite threaded his left arm through a bronze band in the centre, then grabbed a handle near the circumference, in effect strapping it to the forearm and giving a solid grip that didn't sacrifice manoeuvrability. Again, a test on Deadliest Warrior found that a good swing with the edge could deliver a fatal blow to an unprotected head all by itself.

The defining feature of the hoplite however was his huge, heavy shield, the hoplon ("piece of equipment"), which the Greeks called an aspis. It measured almost a metre in diameter, weighed

about 7.5kg, and was usually 25-40 mm

thick. Most of this thickness was the wooden core, but the aspis usually had a bronze skin front and back, and some had a layer of leather as well. It was without doubt one of the most advanced pieces of military tech in the world: the wooden core gave it fantastic energy absorption, while the bronze exterior shrugged off sharp points without letting them dig in. Most important was the grip, known as the Argive grip, whereby the hoplite threaded his left arm through a bronze band in the centre, then grabbed a handle near the circumference, in effect strapping it to the forearm and giving a solid grip that didn't sacrifice manoeuvrability. Again, a test on Deadliest Warrior found that a good swing with the edge could deliver a fatal blow to an unprotected head all by itself.Mostly though it was a defensive implement, not only protecting the bearer thigh to neck, but protecting his neighbour as well. Drawn up in a dense formation the hoplites would overlap their shields, each protecting the man on his left while being protected by the man on his right. The downside of the aspis was its great weight, so great that a man wishing to flee had to cast it aside. This concept was so important to Greek culture that ripsaspis – "one who throws away his shield" – still means deserter, even in modern Greek. On the other hand the sheer size of the aspis also made it a convenient stretcher for the dead, hence the traditional Spartan farewell E tan e epi tas ("With it or on it").

In some periods, the convention was to decorate the shield with a form of Bronze Age heraldry; the shields of the Thebans, for example, were sometimes decorated with a sphinx, or the club of Herakles. The most famous decoration was the capital lambda (Λ) of Sparta, standing for Lakedaemon ("Λακεδαίμων"), the Greek name for Sparta.

All this is fairly common knowledge: what's still causing arguments is how it all worked in practice. Come up with some definitive, once-and-for-all answers about how a phalanx worked, and you'll get tenure and more citations than Erdős. To wit: were the spears wielded overhand, or underhand? Were they primary, repeat-use weapons, one-offs like a medieval lance, or even thrown like javelins? If one of the latter two, was the sword actually the primary weapon? Just how hard was it to kill a hoplite? What were the casualty rates of hoplite battles?

Of these, one of the most important questions is whether a Greek battle was a bloody, stab-happy spear-fight that happened to take place behind a shield wall, or a slogging, pushing shield-fight, like a rugby scrum in bronze. A lot rides on how you choose to answer this question, and each brings its associated headaches. If they were pushing shield-fights, why were deeper formations sometimes defeated by shallower ones? But if they were stabbing spear-fights, why were deeper formations used at all?

Phucking Phalanxes, How Do They Work?

As I said, these days answers are coming. One of those who've done some serious thinking is Paul Bardunias of the Hollow Lakedaimon blog, a Spartan (a real one!) who spends his professional life studying self-organisation in termites. In studying how mindless termites can build a structure as large and complex as a termite mound, Paul realised the same principles applied to phalanx warfare: on a battlefield, one of the few truly chaotic situations human beings can encounter, the range of possible stimuli and responses narrows sharply, and humans start to behave in a way remarkably similar to termites (insert Myrmidon joke here).

In our modern world we tend to imagine very orderly, Napoleonic armies existing throughout history: men standing in squares, marching in locked step, attacking on command, the general directing proceedings from a good vantage point. That concept would've been alien to most of the Greeks, who were at pains to point out the only people who could do this sort of thing were the Spartans.

The Spartans have been recorded as showing up to a battle in phalanx, only to have the opposition line up and then withdraw from the battlefield, intimidated by what they saw before them. The phalanx allowed them to win the victory, but without bloodshed.It's not hard to understand why: in 371 the Greeks were only some metallurgy and a few farming tricks away from a Neolithic tribe. Their soldiers were mostly farmers or potters who probably went years without dusting off their armour. They arrived at the army's mustering point as virtual family units, no different to if your local alpha male (don't pretend you don't know one) went around your block doorknocking for volunteers to join his Red Dawn-style resistance group. In other words, they were militia, and so their organisation was less an orderly square and more a vague blob. Each man knew roughly who he had to stand beside and little else, but at the time that was enough. As Bardunias likes to ask, who organises a Mexican wave?

With this crowd-physics approach, Bardunias is able to paint a pretty vivid picture of how a phalanx entered battle, and reveals the shield-vs-spear issue is not a question of either/or, but when for each.

Once the men were in place, in most armies their leaders would walk along the front haranguing them. Spartans relied on encouragement between hoplites and sang to each other in the ranks. In a prelude to the battle to come, the opposing light troops or cavalry could skirmish in the space between the opposing phalanxes. When the light troops had been recalled and the sacrifices had been taken, the commanders had trumpets, salpinx, sounded and men began marching towards the enemy... As they advanced the hoplites sang the Paian in unison, aiding morale and coordination.(Fun fact: research has shown that playing music together can actually synchronise people's brainwaves. If you accept the voice as a musical instrument, then it's no wonder the Paean was so effective at getting everyone, literally, on the same wavelength.)

At this point men would bring the shield up in front and the command would be passed for the first two ranks to lower spears... When the armies were less than 180 m apart, most phalanxes shouted an ululating war cry to Enyalius and charged at the run. They did so for psychological reasons, both to channel their nervous tension into the attack, and frighten the enemy with their rapid advance. Coordinating the charge along the chain of units that made up the phalanx seems to have been difficult, and gaps often formed as some hoplites charged sooner than others. Variation in speed of advance could lead to one section of the line leaving the rest running to catch up. The result is that a phalanx rarely encountered its opposite as a unified front. For these reasons Thucydides tells us that large armies break their order are apt to do in the moment of engaging.

Thucydides also describes phalanxes drifting to the right as they advanced because men sought to shelter their unshielded right side... But it is likely that the whole phalanx contracted as well. Bunching as they moved would have been a natural reaction of frightened men as it is with other animals.

The two phalanxes would have slowed as the enemy loomed large. The same fear that drove them to charge would keep them from running blindly into a hedge of enemy spears. Because disorganized men charging at speed into the enemy results in a weaker mass collision, there is no reason why men could not halt at spear range rather than after crashing together. If men did not regularly stop and fight with their spears, then it is difficult to understand the many references to one phalanx breaking when the two had closed to spear range. Hoplites converging at even a modest 5 mph would cover this distance in less than half a second.

What followed was described by Sophocles as a "storm of spears." While taunting their foes, the first two ranks of the opposing phalanxes would assume the ¾ stance common to most combat arts and strike overhand across a gap of about the 1.5 m reach of a dory. The overhand motion results in a much stronger thrust than stabbing underhand, and would be less likely to impale the men behind. When striking from behind a wall of shields, the overhand strike not only ensured that your arm was always above the line of shields but allowed a wide range of targets. During this combat adjacent hoplites were mutually supporting, and a man could be killed through the failure of those alongside him. The second rankers would have attacked where they could reach, but their spears also acted to defend the men in front.

Spear fighting could go on for some time, and often one side must have given way as a result, but we know that battles could move to close range. It is difficult to imagine men easily forcing their way through multiple ranks of massed spears, but we know that hoplites often broke their spears, and a sword armed man would be highly motivated to close within the reach of his foe’s spear. Once swordsmen closed with the spearmen somewhere along the line, phalanxes could collapse into each other like a zipper closing as spearmen abandoned their useless spears in favor of their own swords.

Are We Not Men?

This is where I weigh in: the problem here is that Bardunias isn't factoring in the psychological aspects of killing on the battlefield. In fact, before the end of WWII, nobody did, not even the military. This oversight was corrected in time for Vietnam, and now, thanks to Lt. Col. Dave Grossman's book On Killing, the basics are now public knowledge. To summarise: when looking at historical battles we tend to assume each side is comprised of Terminators who'll go forth and unflinchingly destroy everything in their path. 'Fraid it just ain't so. Soldiers in every age are human beings with hearts and minds, and despite what Hollywood and Nietzsche-wannabes will tell you, they're not natural born killers.

When frightened for one's life, the soldier's brain speeds up its processes by shutting down the frontal cortex – the part of the brain that make us human – and runs on the much faster hindbrain that is basically indistinguishable from any other mammal. On this level, most animals have a phobic-level resistance to killing one of their own species – Grossman even cites male rattlesnakes which, although armed with deadly venom and capable of killing each other in an instant, will nevertheless compete for a female via a harmless wrestling match. This goes for humans as well. During WWII it was discovered as few as one in five humans will ever try to kill the enemy, even to save their own lives: the reality of the act, which in intensity, intimacy and nature is the exact counterpart to sex, is simply too horrible to go through with. If they are able to overcome this resistance and actually kill someone, as the ongoing cost of the Vietnam War illustrates, the result is crippling psychological trauma. Only around 2% of soldiers are apparently unaffected, and these will usually show signs of being "aggressive sociopaths." So 98% of your soldiers will be traumatised by killing, and the other 2% were crazy when they got there.

A worthy lesson, however obvious: war is really, really fucked up.

With Grossman's principles in mind, it becomes clear that shield-pushing probably decided more battles than the storm of spears, simply because you could actually get the average soldier to do it. Similarly, this is why I don't believe the wide-open Chalcidian helmet was much of a disadvantage. Intuitively it might seem the Chalcidian design left the face much more exposed, but stabbing a man in the face is such a repulsive act that I imagine very few would ever have tried it. Circumstantial evidence shows that the Romans stuck with an open-face design for the thousand-odd years they were a power, and despite all the close-up Legion fighting they did, it never seems they felt they were leaving a hole in their defence.

This also sheds new light on the Sparta's choice of swords. Slashing comes much easier than stabbing, the prospect of several inches of cold steel sliding into someone's guts being rich in sexual overtones and producing deep revulsion. Even though it was probably almost useless as an instrument of death, a kopis would nevertheless be a more effective weapon for the 98%, simply because its slashing action meant it would actually get used. Conversely, the xiphos probably worked best in the hands of the few genuine killers in the ranks: history records that the groin and the throat were the preferred targets of the tenacious Spartans, and Bardunias notes a downward stab, alongside the neck into the chest cavity, can be seen on a vase in the Museo Nazionale de Spina.

If the WWII percentages hold then only 20% of hoplites would've actively tried to kill an enemy, but that doesn't mean the rest were dead weight. Even if they got squeamish and didn't actually try to kill anyone, a whack to the helmet with a dory would still be distracting and demoralising. Even a half-hearted strike could leave a nasty wound, especially when the arms, shoulders and neck were so exposed. Between the love-taps, the fake-outs, the poking, the prodding and the knocking aside of incoming spears, it's likely nobody in the front couple of ranks made it home without some impressive scars.

A Crush of Crowds

The Big Question with a pushing shield battle – which the Greeks called othismos – also comes from the nature of crowds. If you've ever been to a major concert you'll recall that they're surrounded by security and medical personnel ready to pull out anyone trapped against the fence. The amount of force a crowd can subject you to can be truly frightening: the rule of the thumb among the experts is that you only need to stack people four deep to generate enough pressure to kill an unprotected human, just enough to disable the diaphragm or, in more extreme cases, collapse the lungs. And remember, these are normal, non-malicious people not even aware they're causing you harm; we can only imagine what might happen against a foe genuinely out to do you in.

This "rule of four" explains the standard phalanx depth of four shields, but it opens up major questions about how anyone could survive being in the front rank of a phalanx eight, twelve or – as we will see – even more shields deep. If you were stuck in the middle of that, how the hell were you supposed to be able to breathe? For a while I assumed this was the true purpose of the thorax, keeping your chest from being compressed, since it didn't really protect the neck or shoulders where they were most vulnerable (and some concurred). But the pressures involved and the use of bronze now make that seem unlikely to me – you might as well stick a can of baked beans in a vice.

Paul Bardunias even has some numbers (elsewhere backed up by graphs):

Unless the men closed up laterally belly to back, which is impossible with a meter-wide aspis, the sustained, grinding pressure on their right shoulders would force them to collapse forward until they were parallel to their shields and the men in files were packed belly to back. Once they achieve this spacing and stance, they can be compressed no further and have achieved what specialists on crowd disasters term a “critical density”. This is defined as at least 8 people pressed together with less than 1.5 m of spacing per person. By simply leaning against the man in front like a line of dominoes, 30-75 % of body mass can be conveyed forward in files, and just three leaning men can produce a force of over 792 N or 80 kg. Shock waves can travel through such crowds, and less than 10 people have been shown to generate over 4,500 N or 450 kg of force...That one detail was the design of he aspis itself. Look at it again: deeply dished, with a unique flat rim. Brilliant, isn't it? No wonder this was the defining piece of gear of the hoplite, it was the one thing you needed to survive the crush of a phalanx. When the pressure overwhelmed your shoulder muscles and the aspis dropped flat against your belly, at no point was it actually resting against your belly. Instead, that flat rim rested against your clavicle at the top and your thigh at the bottom, leaving the diaphragm free to keep you breathing (as crudely but effectively diagrammed here). I wonder if the man who made the first one even realised what he was doing?

A file of hoplites, even 8 deep, could produce enough force to kill a man through asphyxia. A force of 6,227 N will kill if applied for only 15 seconds, while 4-6 minutes of exposure to 1,112 N is sufficient to cause asphyxia. The heretics would be correct in assuming that pushing by deep files was not survivable, but for one detail.

With that mystery apparently sorted, the hoplite was freed to get on with the business at hand – which was, ironically, mostly doing nothing. When the phalanx reached this level of pressure human muscles were dwarfed into insignificance: what mattered was being there, leaning forward on your comrades, applying your weight, not your strength, to the phalanx. This explains the Spartan preference for a slow, measured advance rather than a charge, because:

Dense packing is far more important to transfer a strong, sustainable force, even if it occurs at slow speed... The crowding of othismos and periods of active, intense pushing could last for a long time as men leaned ahead like weary wrestlers. It is now that rear rankers could bring their pressure to bear. They would close up swiftly, initially supporting those in front, but then gradually pushing them tight together. All such moves have to start at the back of the files, there is no point at which a man could simply jump back and his enemy would fall forward. Just as packing was gradual, so is unpacking. The whole mass would move in spasms and waves like an earthworm.Or as another writer put it: "In the othismos I'm not even sure how accurate the term 'pushing' is, its more like stumbling forward in a mass. That mass will be impossible to resist by men, however strong pushing in an uncoordinated manner." The Greeks were very good at this sort of fighting, and it stood them well in the Persian Wars; at Thermopylae, most Persian soldiers were apparently killed by asphyxiation or being pushed off cliffs than by spears.

Which leads us rather neatly to the question of casualties. If you're wondering what kind of medical care a wounded hoplite would receive, the answer is, "surprisingly good." Because phalanx battles were brief there was a good chance a wounded man would be picked up in the Golden Hour, the crucial sixty minutes following a traumatic injury that usually determines survival. From there, Hippocrates' works describe various types of suture, and the Greek physicians had access to mekon, the syrup of poppies. The only thing they didn't do especially well was deal with infection: Hippocrates did note that spilling wine on a wound seemed to reduce inflammation, but he was largely ignored, because most Greek physicians were very happy to see an infection develop, actively encouraging pus formation and distinguishing some varieties as "benign." This sounds like madness, blasphemy, until you remember while inflammation meant infection, no inflammation meant gangrene, which was much worse.

There's also the myth that because Greek battles so closely resembled an NFL match, they weren't much more dangerous than an NFL match either. We can lay that one to rest. Peter Krentz wrote a brief but thorough chapter on casualties in hoplite battles, imaginatively called Casualties in Hoplite Battles, and the good news is, because they were citizens and valued by their community, the Greeks raised war memorials listing the dead by name. The bad news is that these memorials are two and a half thousand years old, so they're usually eroded and broken, leaving the lists incomplete. Nevertheless, using what we have Krentz was able to crunch some pretty definite numbers.

The defeated army rarely lost more than 20%: typical is 10-20%, the average approximately 14%. The winning side never lost more than 10%: typical is 3-10%, the average approximately 5%... On the other hand, the Greeks (as Thucydides says specifically of the Lakedaemonians) did not usually pursue far once a battle was decided. This reluctance to go too far in killing enemy soldiers once their line had broken stemmed as much from the fear of a reversal if the troops dispersed as from a gentlemanly hesitation to kill fellow Greeks; but it did mean that the losers' losses, while twice or three times as heavy as those of the winners, were rarely more than a fifth of their engaged forces.Since hoplites were similar in arms and armour, I'm guessing they traded casualties evenly in the actual battle. Since the winners didn't suffer any pursuit but still tended to suffer 3%-10% casualties, we can probably regard this as typical of hoplite battles. For comparison, the safest war the U.S. ever fought was Desert Storm, where only 0.075% of their soldiers were killed, less than would've died in car accidents had they stayed home. At the other end of the scale was their Civil War, from which Ulysses S. Grant emerged with a reputation as a merciless butcher, with a career average casualty rate of just over 15% (although this was below the Union average, and that celebrated military genius Lee emerged with an average above 20%). This is a worthy comparison to Greek hoplite war in only one respect: both sent actual citizens out to do the fighting. Since they weren't using despised minorities as cannon fodder (like the the Scots post-1745 or, for that matter, Latinos in today's U.S. Army – Gary Brecher has said the casualty lists from Iraq read like the timesheets at your local burrito shack), that made both the Greeks and the Union rather more sensitive to the blood they were spending.

Were losses in the truly typical battles, such as Delium and Mantinea, "remarkably light"? Modern opinions may vary, but what we really want to know is what the Greeks thought. I suspect that, in the small world of the Greek polis, the death of even 5% of the hoplites sent out to fight would seem a significant loss. The standard rhetorical description of a battle included a statement that "not a few" or "many" fell on both sides, as we can see from Diodorus.We can see therefore that hoplite battles were heavily dependent on morale, or perhaps more accurately, nerve – it was paramount that the phalanx never break, or you were going to suffer Grant-level casualties to a fairly small and affluent part of your society. This is where the Spartans really shone. Apart from the fact that they had an actual death wish and preened like teenage girls before battle, oiling their hair, trying out fetching new styles, putting little baubles in their ears, anything to die young and leave a beautiful corpse... apart from all that, from childhood they were being conditioned by sick games like running a gauntlet of whips to snatch a piece of cheese, so they learned early on the road to reward lay through a valley of pain. Their whole life was geared towards preparing for close-up, face-to-face violence, and given the importance of holding the line despite immense pressure, wounds, and the temptation to help a fallen comrade, the Spartan emphasis on duty, resisting pain and seeking death starts to make real military sense. We can only imagine how demoralising it must've been to go head to head with an army that, no matter what you threw at it, just would not flinch.

|

| Note: the guy in the centre is wearing a helmet pretty close to the Chalcidian type worn at Leuktra; compare and contrast the Corinthians worn by the guys on either side. |

So it was that the Spartans remained the absolute masters of this kind of war – right up until the Thebans handed their arses to them.

Greek Love: Thebes and the Sacred Band

Thebes, the real Thebes, the one Herodotus called "Seven-Gated Thebes" to distinguish it from the one in Egypt that was actually called Wasat, was a polis on the Boeotian plain. According to myth it had been founded by Kadmus on the orders of Apollo: the chosen site was guarded by a dragon sacred to Ares, which Kadmus had to slay, but in the process the dragon killed all his friends. Kadmus despaired at how he was going to found his city – until Athena leaned over and whispered to plant the dragon's teeth, which sprouted into a mob of warriors, armed and ready for battle. By throwing a stone between them, Kadmus tricked into fighting each other until only five remained: with these he founded his city, and gave his name to the citadel, the Kadmeia. The other Greeks would've done well to remember this founding myth: thanks to its central location many crucial battles had been fought in Boeotia, to the point it was sometimes called "the dancing floor of Ares."

Then again Greeks had some weird quirks, such as a possible inability to see the colour blue, and a habit of carrying coins in their mouths. One of Thebes's quirks was a reverence for Greek Love and the naked male form that even other Greeks found remarkable, so it's not too surprising it was a forward-thinking Theban who turned to an idea that had been kicking around for some 400 years. Homer had speculated that an army of close kinsmen would fight brilliantly together, since their bond of love would be so strong it would make them invincible; failing that, an army of lovers might achieve the same ends, since no man would want to disgrace himself in front of his boyfriend. Realising Thebes would need its own elite unit, its own SEAL Team Six, Gorgidas turned his grey matter to the implementation of this idea.

His solution was to hand-pick 150 pairs of young men who happened to be lovers and assign them to a standing unit: the Sacred Band. In ancient Greece, a couple usually comprised of a conservative older man (the erastes, usually translated "lover") and a pretty younger man (the eromenos, or "beloved"), who was usually a teenager. This was intentional, as Plutarch noted: "Their lawgivers, designing to soften whilst they are young their natural fierceness... gave great encouragement to these friendships... to temper the manners and characters of the youth." We shouldn't judge too much: young men are dangerous, and societies have found some strange ways of dealing with them; Saudi Arabia sends its hotheads off to die for Islamic State, while in the West we park them in front of a Playstation loaded with a Modern Warfare disc and hope for the best. Buttsecksing them instead was probably an effective way of keeping them in line. Xenophon even wrote that many of them solemnified their relationship in a religious ceremony – virtually a marriage – which, since the cult of Herakles was especially strong in Thebes, took place at the shrine of Herakles' lover and comrade-in-arms, Iolaus.

|

| Yes, him. |

The chosen 300 were at first dispersed along the front rank of the whole army to add extra oomph to the Theban offense; it was Pelopidas who decided to make them a separate unit, thinking it would better show off their courage. It would not be long before they were showing what they could do, winning their first victory at Tegyra in 375. Retreating from a failed attack on Orchomenus, a Boeotian polis that remained stubbornly loyal to Sparta, the Sacred Band virtually tripped over an army of two Spartan companies comprising some 1,000 to 1,800 men. Heavily outnumbered, one of the Band wailed, "We have fallen into our enemies' hands!" to which Pelopidas did his best Chesty Puller impression and said, "Why any more than they into ours?" He ordered the Band into an abnormally dense formation, sent his cavalry to create some havoc, then rammed the Sacred Band straight into the Spartan ranks. The thin Spartan line couldn't resist this concentrated punch and the phalanx was broken, leading to panic in the ranks and the unheard-of phenomenon of Spartans tossing aside their shields and running for the hills. The garrison of Orchomenus was too close to risk a follow-up chase, but the battle was won, and the Sacred Band were left holding the field with a dangerous new idea taking life in their heads – that the Spartans could be beaten.

The Campaign

|

| Regions of Greece, each basically its own country |

Crucially, it was the Corinthian War that began the erosion of the dominance the Spartans had enjoyed since their victory over Athens in 404. Sparta didn't have the manpower to garrison Greece, and the agoge didn't exactly breed master diplomats, so the Corinthian War was ended by an armistice and not a victory – one dictated by a Persian mediator rather than a Spartan victor. The Spartans and Persians had actually become pretty tight since the Persian Wars, the kings of Persia coming away with such a healthy respect for Greek heavy infantry that they'd got in the habit of hiring Spartans as mercenaries: Xenophon's famous March of the Ten Thousand was a ploy to tell such a dazzling story that everyone would forget he'd been busy serving a Persian pretender.

So the Persians knew exactly what they were doing when they bargained successfully for control of Ionia (the Greek coast of modern Turkey), in return for declaring every polis in Greece nominally independent – then empowered the Spartans to enforce the treaty, knowing they were too weak to do the job. This document, known as the Peace of Antalkidas, created a state of cold war rather than a genuine peace, and condemned the Greeks to another generation of Greek-on-Greek bloodshed.

It didn't take long to unfold. Under the pretext of enforcing the independence of the little fish, the Spartans ruthlessly broke up any coalition they saw as a threat. Disloyal allies were punished severely – Mantinea, for example, refusing to contribute to the common military effort in 385, had its mudbrick walls washed away by a redirected River Ophis and was broken up into its five component villages – while the Persians, free of Greek interference at last, solidified their hold on Ionia and went onto conquer both Egypt and Cyprus. But no polis suffered more than Thebes. Sparta insisted on independence for all the cities of Boeotia, right down to Plataea, forcing the breakup of the Boeotian League. The Thebans were displeased to say the least – Boeotia was their stamping ground, no-one else's. Their agitation triggered the largest of Sparta's interventions in 382 when, on the way to a completely different crisis point at Olynthus, the Spartan commander Phoebidas allowed himself to be talked into meddling by the Theban aristocrat Leontiades. Taking advantage of civil unrest, Phoebidas seized the Kadmeia and installed a pro-Spartan puppet regime, headed by this same Leontiades. For this unauthorised action Phoebidas was fined and relieved of command, and his clumsy realpolitik only turned the last of Sparta's supporters against them – but Sparta nevertheless left his arrangements in place.

Ironically, the men who would be the doom of Sparta had already been brought together by the Spartans themselves: Pelopidas, and Epaminondas. An interesting character, Pelopidas had been born wealthy, but refused to dress himself better than the lowest beggar in the city, and ruined his estate by constantly handing out money to the poor. Once, his friends tried to argue to him that since he had a wife and children, money was necessity: he just pointed to a nearby beggar named Nikodemus and replied, "Yes, necessary for Nikodemus." A brave soldier, he'd also been at Mantinea in 385, fighting among the Theban contingent of loyal Spartan allies, where he'd received some nasty wounds.

Pelopidas, after receiving seven wounds in front, sank down upon a great heap of friends and enemies who lay dead together; but Epaminondas, although he thought him lifeless, stood forth to defend his body and his arms, and fought desperately, single-handed against many, determined to die rather than leave Pelopidas lying there. And now he too was in a sorry plight, having been wounded in the breast with a spear and in the arm with a sword, when Agesipolis the Spartan king came to his aid from the other wing, and when all hope was lost, saved them both. (Plutarch)If he'd seen what was coming, Agesipolis almost certainly would've just let them die. As it was, Pelopidas and Epaminondas survived and fell into a bromance that lasted the rest of their lives, became partners in crime for the next 20 years, aided no end by Pelopidas's habit of tossing money to the poor. Since the Spartans were oligarchs, their supporters throughout Greece also tended to be oligarchs, and the faction the Spartans had placed in power in 382 was mostly comprised of wealthy blue-bloods. In contrast, Pelopidas's largesse made him a leading light of the democratic faction, giving him lots of popular support despite fleeing to Athens to escape the coup. With the conniving of Epaminondas, who was allowed to stay in Thebes because, according to Plutarch, "his philosophy made him to be looked down upon as a recluse, and his poverty as impotent," Pelopidas and the populists began planning a comeback.

|

| Epaminondas |

In 379, during the winter, a group of twelve Thebans led by Pelopidas infiltrated the city and, together with a force of Athenian hoplites, roused the rabble and surrounded the Spartans in the Kadmeia. Realising they couldn't win, the Spartans bargained for their lives, surrendering on the condition they be allowed to march away unharmed. Their wish was granted, and Thebes was returned to the Thebans. Now a boeotarch (a statesman and general of Boeotia), Pelopidas turned his attention to restoring Theban control of the region.

When news of the Theban uprising reached Sparta, an army under Kleombrotus was dispatched to squash it, but turned back without engaging. Kleombrotus was one of the two Kings of Sparta, of the Agiad dynasty, the same line as Leonidas (his great-grandfather had been Leonidas's nephew). Some have read his actions as those of a Theban sympathiser: personally I can't quite credit that of a Spartan, but it does seem suspicious that he didn't even give battle, and that another army under the other Spartan king, Agesilaus II, had to be sent instead. Again the Thebans refused to meet them in open battle, building a trench and stockade outside Thebes and daring the Spartans to attack. Once more they declined, electing to ravage the countryside instead, but this approach was less effective against Thebes than it had been against Athens forty years earlier. Back then, the Spartans had promised, "Your cicadas will chirp from the ground," and torched the olive groves that were the foundation of the Athenian economy. With their cattle-based economy, however, the Thebans found moving their herds to safety wasn't difficult, leaving nothing but open grassland for the Spartan torches. The economic disruption was minimal, and eventually Agesilaus got bored and took his army home, leaving Thebes independent.

Flushed with victory, the Thebans under Pelopidas began a whirlwind of diplomacy – invasion, bargaining, bribery, threats – to bring the rest of Boeotia back under their control. Alarmed, the Spartans invaded twice more (in 378 and 377), both times under the pretext of enforcing the Peace of Antalkidas, with little effect. The Thebans at first shied away from fighting them, but some skirmishing was inevitable, and in the long run it proved excellent practice. In the words of Plutarch: "they had their spirits roused and their bodies thoroughly inured to hardships, and gained experience and courage from their constant struggles."

But war-weariness was setting in: a feeble attempt at peace was made in 375, but by then Thebes pretty much had everything they wanted anyway, back in the saddle at the head of another Boeotian League – this one run along much more democratic lines than the previous Theban empire. All Boeotian men, whatever their affluence, were now members of an Assembly convened at Thebes to vote on matters of policy: the seven boeotarchs (one from each of the seven districts, of which Thebes controlled three) were elected by and answerable to this Assembly. Padding this power base, other districts hot for democracy started allying with them: Euboea, Akarnania, Phokis, Thessaly, Arkadia, Achaea.

Thebes was now a major power in Greece, and making Sparta's job that bit harder, by 373

Athens was starting to climb out of the black pit of defeat as well. Then in 372 Thebes destroyed Plataea and the fortifications of Thespiae, and achieved the unthinkable: putting Sparta and Athens on the same page. Both were bankrupt, overstretched and now very scared of the Thebans, and therefore desperate to renew the peace. In June of 371, the Spartans invited everyone over to their place to hammer out a peace deal.

Serving as a boeotarch that year, Epaminondas led the Boeotian delegation and agreed to Sparta's terms, signing the treaty in the name of his polis. Overnight, however, he seemingly had a rethink: only Athens and Sparta stood to gain from taking a breather, so the next day he insisted he be allowed to sign not just for Thebes, but for all of Boeotia. The sheer cheek of it gave Agesilaus an eye twitch: here he was, asking to sign a document forbidding confederations in the name of his confederation! Agesilaus testily refused, insisting every polis in Boeotia remain independent. Epaminondas countered that in that case, the cities of Lakonia should become independent as well, and at last succeeded in provoking his host to puce-faced rage. Agesilaus scrubbed the Thebans from the treaty and threw out their delegation, Epaminondas and his posse returned to Thebes, and both sides mobilised for war.

The Battle

Kleombrotus was already in the field, at the head of an army in Phokis, a region to the Boeotian northwest. At his command were some 10,000 hoplites – only 700 of them actual spartiates, Spartan citizens honed by the agoge, with the numbers made up by their Peloponnese allies – plus 1,000 or so hippias, the rather inferior Spartan cavalry. This was a huge force by ancient Greek standards: one gets the feeling the Spartans were throwing in everything they had. The ephors sent them their marching orders, this time the aim being the destruction of Thebes once and for all.

The opposition comprised some 7,000 hoplites (4,000 Theban, 3,000 Boeotian) and 1,500 excellent Theban horsemen, all under the command of Epaminondas. He led the bulk of his forces (some 6,000 hoplites) to a defensive position between the city of Koroneia and Lake Kopais (tricky to find on a map, as it was drained in the 19th Century); another 1,000 hoplites were dispatched to set up an ambush in the pass at Mt Helikon, with another small force sent to guard the pass at Mt Kithaeron against possible reinforcements from Sparta itself. In a move Guderian would've admired, Kleombrotus bypassed the Theban defense by marching from Ambrossos to Styris and then southeast to Thisbe and all the way down to the Corinthian Gulf at Kreusis, where he captured twelve triremes. At a stroke he'd turned the Theban defense, opened up a clear path to Sparta, and placed himself in a position to threaten Thebes itself.

But a clash with a smaller Theban force had alerted Epaminondas to his progress, however, and the Thebans decamped and hurried south to place their army between Kleombrotus and Thebes before it was too late. They caught up with him south of the ruins of Thespiae, where the Spartans had camped on the high ground overlooking a tiny village called Leuktra.

|

| The march to Leuktra: this is just to give you a basic idea; I have no idea where river crossings would've taken place, for example. |

At first neither side was eager for a fight. Kleombrotus had avoided battle until now, probably out of a need to avoid casualties more than any admiration for Thebes. The Spartans had never numbered more than 8,000 actual spartiates, even in their heyday; today, in 371, that number had dwindled to just 1,200, the result of constant warring, merc duty in Persia that kept them away for years at a time, and the custom of not letting spartiates move in with their wives until they'd turned 30, all of which hit birthrates like a sledgehammer. Nevertheless, against his better judgement, Kleombrotus had to stand and fight because his senior officers were darkly hinting he could face indictment by the ephors if he again returned to Sparta without wetting his spear.

Epaminondas's Boeotian allies were likewise skittish, a little overawed to be facing spartiates in a stand-up battle. The Thebans themselves, however, were keen. Eight years of on-again off-again skirmishing had given them plenty of time to learn Sparta's weaknesses, and they were no longer intimidated: bluntly, familiarity had bred contempt. For several days the boeotarchs debated giving battle on a field where they were outnumbered 3-to-2, but Epaminondas knew if they didn't fight now, his Boeotian allies would go home and defend their own cities, and the Spartans would be free to isolate and besiege Thebes. Knowing it was now or never, Epaminondas argued for giving battle, and got his way. On 6 July 371, the Theban army marched out and took up position opposite the Spartans.

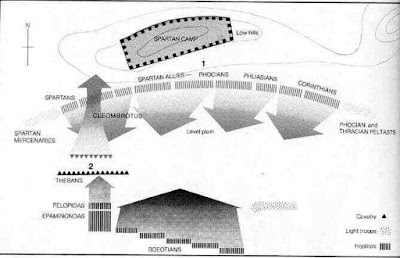

Epaminondas had a plan. He knew how the Spartans would form up their line, because they always did it the same way, with their best men on the right wing. This was usually where you needed your steadiest men, because the extreme right had no neighbouring shields to hide behind, and if they panicked they risked undoing the whole phalanx. Hitherto this hadn't mattered much, because both sides formed up the same way, so their veteran right wings usually overwhelmed weaker left wings. Epaminondas deliberately broke with tradition: despite the huge numbers of allies on the field, he could see the real fight was between actual Thebans and actual Spartans, and in that fight he had a huge advantage, 4,000 to 700. Even better, his boys had been raised on a diet rich in beef, and that had made them big, strapping, solid motherfuckers. By contrast the agoge had raised the Spartans in a state of near-starvation, and although it'd made them tough, it'd left them rather small and wiry rather than impressively muscular (something else 300 got wrong). In a good old fashioned othismos, Epaminondas knew he had the edge.

So instead of forming up in a simple line, Epaminondas formed up his Thebans not the usual 8 or 12 shields deep, but a monstrous 50 deep – then placed them on the left wing, directly opposite Kleombrotus and his 700 spartiates. He placed the remaining Boeotians on the right flank, where he "instructed them to avoid battle and withdraw gradually during the enemy's attack." The strengthened Theban left, spearheaded by Pelopidas and the Sacred Band, he ordered to attack at the double, while the right flank retreated. He was gambling that his Thebans could defeat the Spartans and keep his less reliable Boeotian allies out of the battle until a decision could be reached.

Never before had a phalanx deployed in echelon formation, nor had the best troops been placed on the left wing, but when he saw the human battering ram Epaminondas was forming up, Kleombrotus was unworried. His spartiates deployed 12 shields deep, this considered, at the time, a good compromise between pushing depth and wide frontage. They were all masters of othismos, drilled and practised in the art of the slow advance, moving with measured tread, every man keeping time to the trill of the flutes, giving the enemy plenty of time to panic. As the battle opened with the skirmishers and cavalry dueling between the two hosts, the Spartans had every reason to be confident.

The superior Boeotian horsemen had the mastery of the opening skirmish, but it was still only a sideshow: a bloody stalemate would've been enough, as long as the Spartan horsemen were prevented from interfering with the Theban column striding forward across the shallow valley. Seeing what was coming, Kleombrotus gave orders to lengthen his own line, exactly as he should've; the rear six ranks of the phalanx attempted to spread out to their right, sacrificing depth for frontage. Once the Thebans were bogged down in a pushing match, his flanks would envelope theirs and a rout would follow.

Except that enveloping thing didn't happen. Abruptly the Thebans kicked up a gear and advanced at a dead run, sacrificing cohesion for speed and closing the gap so quickly the Spartan king didn't have time to think. Coming on at breakneck pace, the Theban spearhead reached the Spartans while still in the midst of their change of formation, caught moving before they could brace themselves for othismos.

Despite that, the Spartans had the best of it early on. Kleombrotus himself was one of the first to go down, Pelopidas and the Sacred Band smashing into his line at the very point where the king and his command staff were standing, directing the realignment. But the Spartans put their backs into it and for a while the massive Theban column actually lost ground, just long enough for the Spartans to recover their king and usher him off the battlefield to die of his wounds. Once the fifty-deep human sardine can repacked itself into a shimmering tide of brazen shields and glittering iron spearheads, however, it was only a matter of time. Slowly the Thebans ratcheted forwards, and with no rear ranks to prop them up, the Spartans steadily lost ground. Although enveloped from both sides, there weren't enough spartiates to make a difference and the Spartan line collapsed. The Theban formation pistoned straight through the Spartan phalanx, and although the remaining Spartans fought stubbornly, in a very short space of time they were either dead or fleeing. The battle was won.

As Epaminondas had hoped, his Boeotian allies never even had to lift a spear: when they saw the Spartans throwing away their shields, the Peloponnesian allies about-faced and marched away without striking a blow. Fight the Thebans? Ha! Epaminondas and the Sacred Band had just liberated them!

As was customary in Greek warfare, Epaminondas made no attempt the pursue the survivors, and sent a herald to the Spartan camp granting them permission to gather their dead. As this was the traditional way of claiming victory, we can only imagine how galling it must've been for the surviving Spartans, long accustomed to granting such permission and not receiving it. They asked if they could collect their dead at the same time as their Peloponnesian allies: Epaminondas, suspecting this was a trick so the Spartans could hide their losses, told them no. Instead, he allowed the Peloponnesians to remove their dead first, so that those remaining would be proven to be spartiates, and emphasise the scale of the Theban victory. And its scale was shocking: Xenophon reported that 1,000 men fell that day, 400 of them elite spartiates. A third of the entire Spartan military had died in a single day, along with their king, a blow from which they'd never recover. Only 300 Thebans had died.

Strategic Outcome

Thanks to a confluence of brilliant tactics, great soldiers and some astounding luck, the Battle of Leuktra was a decisive Theban victory. The defeated Spartans slipped away quietly and were met by the rest of the Spartan army at Aigosthena. After some debate it was decided not to stage a rematch: by then the Thebans had another 6,000 mercenaries on their side courtesy of Jason of Pherae, king of Thessaly, who'd temporarily thrown in his lot with Thebes. Instead the Spartans withdrew to Corinth and from there dispersed to their cities. Agesilaus himself advised that the survivors of Leuktra should not be visited with the full penalty usually handed down to disgraced warriors (to have half their beard shaved off and forced to live among the helots), saying instead that, "the laws should be rested for a day." In truth, with a bare 800 spartiates left, he could hardly afford to lose any more.

The following year, after much dithering from Jason of Pherae and the Athenians, Epaminondas marched on the Peloponnese with the aim of breaking Spartan power forever. He found the peninsula in chaos: the Athenians had held another peace conference and ratified the treaty from last June, this time expanding it to include the cities under Spartan dominance. Taking advantage, the Mantineans had once more unified their villages into a single fortified city, bringing down the wrath of Agesilaus, who took the dregs of his army and besieged them. This angered the rest of the Arkadian cities, who banded together to stop him – thus summoning into being the very confederation he had been trying to stop.

Marching into Arkadia, Epaminondas soon found his army swollen to some 60,000 with volunteers from the surrounding cities. He encouraged the newly-unified Arkadians to build a new capital, Megalopolis, as a power centre to counter Sparta. Then, supported by Pelopidas and the Arkadians, he invaded Lakonia itself: Moving south he crossed the Evrotas River, the Spartan frontier, which no hostile army had ever crossed before, and unable to face him in open battle, the Spartans fell back to defend only their city. This the Thebans didn't even try to capture, instead, ravaging Lakonia all the way down to the port of Gythium (which resisted successfully, having been fortified during the war with Athens).

Epaminondas briefly returned to Arkadia before once more marching south to strike his greatest blow – he marched into Messenia, a region Sparta had enslaved some 230 years earlier, and freed all the helots. Since Messenia amounted to a third of their territory and half of their helots, the liberation of Messenia truly sounded the death knell of Sparta as a Great Power. To make the new, free Messenia permanent, he helped rebuild the ancient city of Messene on the slopes of Mt Ithome, fortifying it with some of the strongest defences in Greece, and put out a call for all Messenians to return and help rebuild their homeland. With their military bled white, their economy shattered, their prestige destroyed and two refurbished and hostile states for neighbours, Sparta was finished.

The Aftermath

The comedic epilogue to the whole saga was the reception Epaminondas got when he returned to Thebes. Instead of being paraded as a conquering hero, he faced a trial arranged by his political enemies for remaining in the field for several months after his term as boeotarch had expired. According to Cornelius Nepos, Epaminondas stood before the jury and requested only that, if he be executed for this crime, his epitaph should read thusly:

Epaminondas was punished by the Thebans with death, because he obliged them to overthrow the Lakedaemonians at Leuktra, whom, before he was general, none of the Boeotians durst look upon the field, and because he not only, by one battle, rescued Thebes from destruction, but also secured liberty for all Greece, and brought the power of both people to such a condition, that the Thebans attacked Sparta, and the Lakedaemonians were content if they could save their lives; nor did he cease to prosecute the war, until, after settling Messene, he shut up Sparta with a close siege.This obviously brought the house down, and while they were still rolling in the aisles the prosecution, turning pale, quietly withdrew their case on the realisation it was that or get lynched. Epaminondas was re-elected boeotarch the following year.

But Greece was still Greece, and the political machinations ground on. Jason of Pherae turned hostile and took Heraklea and thus Thermopylae, and Pelopidas died holding him off at Kynoskephale, the Hill of the Dog's Head. But the Thebans won, and in 370 Jason was assassinated, ending Thessaly's brief-but-meteoric rise to Great Power status.

That left Thebes the strongest power in the Greek world, and not everybody was happy about it. The Athenians, who'd greeted news of the victory at Leuktra with stony silence, even marched alongside the Spartans for one last roll of the dice at Mantinea in 362. In a rerun of Leuktra the Thebans were victorious once more, but this time Epaminondas himself was among the casualties, having lived just long enough to learn he had won the battle. In the end, the ascendancy of Thebes lasted just nine years, and the petty warring had only kept Greece weak until the notorious homophobe Phillip II of Macedon – who'd been kept as a hostage in Thebes in his youth, and had studied the methods of Epaminondas firsthand – could enter the stage of history to bring all the cities of Greece together under one banner.

That battle – the Battle of Koroneia, in 362 – was the last fought by the Sacred Band. All 300 of them died where they stood rather than surrender or retreat, which had quite an impact on the Macedonian king. Surveying the dead, Phillip was astounded to learn this was the famous band of lovers and burst into tears, crying out: "Perish miserably they who think that these men did or suffered anything that was base!" Thankfully, his son Alexander was a bit more open-minded.

And the Spartans? All they had left was their rep, which has survived to this day, but when used wisely that alone could be enough. "If I invade Lakonia," Phillip warned them on his conquest of Greece, "you will be destroyed, never to rise again." The Spartan reply was one of their all-time classics: "If." Phillip left them alone.

And today? As per tradition, Epaminondas erected a monument of enemy shields to mark the site of his victory. In a Greece that has since spent several centuries under the Macedonians, several more under the Romans, then the Byzantines, and finally the Ottoman Turks, a modern monument now stands in the "shallow valley" near Leuktra. So, if you're so inclined, you can go on holiday to Greece and visit the place where Sparta died.

Thanks to the Power of (Greek) Love.