For some, following up the rugged simplicity of the 48-215 and iconic FJ would have presented a conundrum: where to go next? But for Holden, the assignment was all too clear. More of the same, if you please, but with a few more creature comforts and – dare we say it? – a touch more style?

(Aero)built in Australia

I've said before that Australian culture in the second half of the 20th Century was a unique mix of Europe (mostly Britain, but more and more of the Continent as post-war immigration ramped up) and the U.S., so it's somewhat appropriate that the twin starting points for Holden's third offering were the drawing boards at Opel and Chevrolet. Holden called their latest creation the FE – model year 1956, according to their "secret" model code system – hinting that, like a wizard, the car arrived precisely when it meant to. That was an achievement in itself, as the FE was more than just Holden's first new platform since 1948: given how heavily the '48 original had relied on homework from Detroit, it was arguably the first pukka Holden ever, and certainly the first that was truly modern.

|

| The '53 Opel Kapitän: only tangentially related to the Holden and, for war-related reasons, actually much less advanced. |

Most reviews of the FE start by pointing out that it was based on the second-gen Opel Kapitän, with the prototype disguised as a Kapitän during open-road testing. Famously, Opel even shipped dies for some of the body panels over to Australia for Holden's use. Dr John Wright, however, has pointed out that the FE's "Aerobilt" body actually owed little to Opel beyond those panels, and the structure underneath was far more modern than any Kapitän (West Germany was, after all, still rebuilding after the devastation of World War II). And Dr John earned the letters before his name writing a thesis on the history of Holden, which became the basis for his landmark book, Heart of the Lion. He literally wrote the book on this, so we'll treat him like someone who knows what he's talking about.

|

| The core of the FE was another steel monocoque, at a time when plenty of car-makers still relied on chassis rails. |

The Baby Boom was well underway, with the eldest of that troublesome generation now reaching their tenth birthdays, meaning interior space was an ever more urgent priority in family cars. Accordingly, Holden lengthened the FE's wheelbase from 103 to 105 inches, then paired it with a nice low transmission tunnel that wasted none of the created volume. This allowed all six passengers to sit comfortably rather than being forced to stretch out awkwardly, wedging shins under the seat in front. The roofline was also made high enough for the inevitable hat everyone wore when driving in those days. All of this forced the glasshouse area to grow by 40 percent, which provided plenty of all-round visibility, but left the C-pillars so feeble that early production models that happened to be sold into more remote areas found their rear screens popping out as the roof flexed more than anticipated. Extra bracing and double-skin structural parts were rushed through to address it.

Boot space was another huge selling point for a car, and here too form and function came together in a beautiful pas de deux. Fashions had moved toward squarer "shoebox" cars, which allowed Holden to take the boot out to encompass the rear wheel arches in a single stamping, lifting boot capacity by two cubic feet (a 10 percent increase). This also allowed the spare wheel to be stored upright on the passenger's side, where it could be accessed without emptying the entire boot (in an age when punctures were nearly as frequent as fuel stops, that was a perk not to be underestimated. Also, both the boot lid and bonnet were self-supporting on opening, a major quality-of-life upgrade not shared with most of its market rivals). Crucially, Holden stuck firmly by their minimum nine inches of ground clearance, and the design was restricted to short overhangs with a Land Rover-style wheel at each corner, necessary when Holdens were driven on roads that would require an SUV in later days (it's worth noting that the modern SUV hadn't really been invented yet. Things like the Willys Jeep and Maurice Wilks' original Land Rover drove like tractors in those days and were in no way considered passenger vehicles).

|

| One of the FE prototypes used for on-road testing. Note the "Opel" and "Kapitän" badging. |

This is not to say the car was without flaw, however, as there was a major one. "Fe" is of course the chemical symbol for iron, so it's almost poetic that the car's Achilles heel was the creeping cancer of rust. "Iron started as a rock," the saying goes, "so never forget that it wants to go back to being a rock." On this topic, Dr John Wright is unusually blunt:

Holden's anti-corrosion policy until well into the 1970s can be summed-up simply: there was none of any significance. The thinking was that if each Holden part was built of sufficient strength and thickness, the rest of the car would be worn out by the time it was rusted enough to present a problem. Given the road conditions, it was a race for any car on local roads to last longer than it took to rust out. The FE, it must be said, pushed that equation to the limit, as it was line ball in some cases whether the rust got there first.

In other words, the FE was a classic victim of Detroit's philosophy that cars were disposable consumer goods. Take a moment to pour one out for all the early Holdens left at the mercy of the rain...

|

| This FE prototype survived by mounting a museum plinth. |

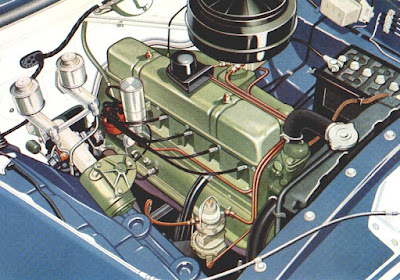

While the body was a revolution, the hardware under the skin was sensibly carried over from the FJ, with only minor improvements. The expected increase in cubes had to wait as the Fishermans Bend engine plant was flat-out just keeping up with demand. For this generation the engine remained the familiar 132ci Grey straight-six, but the demand for more power could not be ignored, so it was fitted with bigger valves and the compression ratio had been bumped up from 6.5 to 6.8:1 (something that could only happen after Australia's fuel quality improved). This was achieved by losing "30 thou" from the head, but stronger pistons ensured the engine's service life was maintained. The end result was a lift in power from 45 to 53 kW, but you had to rev the Grey to 4,000rpm to access it (200 higher than the FJ), and few owners back then drove like that.

In truth, they didn't need to. Where the FJ had provided 135 Nm of torque at 2,000rpm, the FE served up 148 – ten percent more – at just 1,200rpm. In other words, maximum torque was available just 700rpm above idle, allowing the driver to round up sheep at 13 km/h, then accelerate smoothly to overtake on the Hume at 128 km/h, using only the third of their three gears. The non-sychronised first gear was really only used for standing starts, while second was there if you needed to burble around town or climb an especially steep hill (even if that meant the clutch suffered some amount of slip). This, again, goes a long way to explaining why Holden would drag their feet on adding an automatic gearbox to the range – for a long time to come, it just wouldn't be necessary, especially given the dodgy fuel economy of an auto. On that note, the tiny 9.5-gallon (43.2-litre) fuel tank was less than ideal in an era of long-distance travel and limited options for late-night fuel stops. Allegedly the FE offered 30mpg (9.1 litres per 100km), but that disappeared in a hurry with a full boot or trailer.

|

| The engine bay might've been virtually identical to that on the FJ, but "no surprises" was far from a losing strategy in those days. |

Steering feel was improved by swapping out the old worm-and-sector rack for a new, fully-sealed recirculating-ball design, as favoured by Detroit. Apart from reducing steering effort, it was outstanding at isolating road shock, no small consideration on Australia's rough roads. This was paired with a new front anti-roll bar as standard, added by Holden to counter the FJ's tendency to tail-happy oversteer. The sharper steering rack was countered, however, by a revised wheel-and-tyre combo. Holden had fitted the FE with wider 4.5-inch wheel rims, which were now 13 inches in diameter instead of 15. This allowed the fitment of higher-profile "balloon tyres", which came with the dual advantages of off-road performance and maintaining the FJ's 15-inch overall wheel diameter, allowing the carryover of the previous 3-on-the-tree gearbox... at the cost of extra sidewall flex and vague steering feel. It was a problem that wouldn't go away until Holden finally sorted out its sports sedan heritage in the late 1970s, but here in the mid-50s the bias toward off-roading was probably the right decision.

Other changes included replacing the old 6-volt electrics with a beefier 12-volt system, which necessitated a Lucas generator and voltage regulator. This meant stronger headlight beams (important with no shortage of roos on the road at night), and a quicker turnover on ignition. The wipers, however, remained vacuum-operated, meaning they slowed to a crawl if you put your foot down to overtake on the highway. The only real weak point in the mechanicals was that the radiator was too small: it was just about adequate when new, but any loss of capacity as the car aged would see the problems multiply in a hurry, and FE Holdens stranded at the side of the road with their bonnets up soon became a staple of hot summer days.

|

| The interior had a fifties doo-wop pleasantness about it. Apparently, the number one single that year was Johnnie Ray's "Walking in the Rain", which fits the mood perfectly. |

The new key-start ignition had four positions – Lock, Off, On and Start – which meant a Holden finally offered some basic level of thief-proofing, and although the change from floor-mounted to pendant-type pedals is often talked about, it probably didn't mean all that much beyond leaving more space for the feet on a long cruise. The dash was all-new, with a large centre-mounted radio speaker grille with decorative metal knobs, full-circle horn ring, relocated instruments and a larger glovebox featuring cup holder recesses in the lockable lid. Nasco options included reversing lights, windscreen washers, and a front screen demister. The workhorse Standard sedans, utes and panel vans all got ordinary PVC seat covers – only the tarted-up Specials scored the FJ's Elascofab (also a kind of PVC, but with a very grainy finish that was supposed to look like leather as used on the 48-215). This being the era of Mid-Century Modernism, when the prevailing belief was that we could improve on nature, the easily-cleaned and sun-resistant vinyl was viewed as an advance over the leather of yesteryear, which shrank and split in the Aussie sun before much time passed. With an awful lot more cars now on the road, the Special also came with indicators, with the rear blinker flashing the stop light. It was therefore one of the first Holdens to spare its driver from the horrific arm injuries that could result from the compulsory hand signals if you didn't have them.

Styling by Jetsons

When the "new-look" Holden made its first public appearance in Collins Street, Melbourne on 30 July 1956, crowds thronged for a glimpse. And no wonder: Holden was a part of GM, and at the head of GM Styling was the legend himself, Harley Earl. Earl was the man who made full-scale clay models and the concept car standard parts of the automotive design business, and the hallmarks of his designs were tailfins, chrome and bullet-shaped appendages (like brake lights and indicators). It was a design language meant to evoke the glamour of the jet fighter and the rocket – Cold War-chic, we might say? – and it was this design language that Holden had to incorporate into the FE.

The problem was, true to our British colonial origins, Holden's styling department at this time comprised of a bloke in a shed. The bloke was Horace Alfred "Alf" Payze (assisted by a team of talented Aussie draughtsmen); the shed was one of the small outbuildings dotted around Fishermans Bend. Payze was 43 and, like so many of his generation, had seen his career put on hold by the Second World War. But he'd emerged one of the few Australians with any experience in this field and, because sheet metal requires so much tooling to manufacture, forcing any new car's styling to be locked in very early in the design process, Payze began work on the FE barely three years after the original Holden had been launched back in 1948. His mission was to square the Detroit trend toward low, streamlined cars designed for the new American freeways with a very conservative local market that rejected anything that didn't have a function, or that would easily get damaged and fall off – and he had to do it without in any way lowering the ride height. To his credit, he absolutely nailed it.

|

| The shape of inspiration. The one they all wanted, then as now, was the two-door Bel Air with V8 motor. It's easy to see where Payze got his ideas. (Source: Amazon.) |

The shape that emerged looked, not coincidentally, like a scaled-down 1955 Chevrolet. Take a moment to drink in the details, however, and you'll soon realise that none of the Chev's actual features had been carried over: the FE was an interpretation of Harley Earl's styling cues, not a copy, filtered through Australia's more conservative (the unkind might say, less tacky) palate. Even the basic FE came with that shiny plunging radiator grille, chrome headlight surrounds and wrap-around bumpers, and the Special got you an extra strip along the front quarter panel and door, plus "Special" badging around the rear. It had taken real foresight to reckon where Australia would be by 1956, and it was by no means guaranteed that by the time the car actually went on sale the locals would be ready for this much chrome... but they were, so the car was an instant hit.

And since Holden's paint shop continued to lift their game, the FE launched with a new range of colours including Ocean Mist Green, Teal Blue, Lockhart Cream, and the not-at-all-PC Gypsy Red. If you really wanted to turn heads, Specials even came with two-tone options such as a pale green Ocean Mist body with darker Huron Green roof. The most common colours appear to've been Teal Blue, or Teal Blue with an Elk Blue roof, which may have accounted for about a third of all FEs produced, but we won't get into the arguments over that. Although Holden's nitro-cellulose Duco was pretty good for the time, these bright colours needed constant attention to keep shiny and would go chalky if left in the sun.

There was no hero colour, to use the terminology of a later era, but there was a special advertisement in the 5 June 1956 edition of the Australian Women's Weekly. Even in those days, when gender roles were rigid and restrictive, few would've undertaken such a major purchase without consultation with their other half, so Holden sensibly recognised the value of advertising to women. In this case the slogan was, "More beauty for your money," and they chose to showcase it with an example finished in Moroccan Tan and Egret Ivory. Presumably Holden's marketing team thought this was the most striking combination, and after you've taken a gander at Cara Pearson's restored FE on Street Machine, it'll be hard to argue that they were wrong...

The Model Range

There were seven distinct models in the FE range: the Standard, Business and Specials sedans, the workhorse utility and, as of May 1957, the panel van, at last edging out FJ van production. That it was the sleekest van Australia had yet seen was far less important in 1957 than it would be in later eras – the day when panel vans would be bought by young adults (usually up to no good) was far in the future. In 1957 they were still being purchased as an entry-level dual-purpose family and work vehicle, so it was common for buyers to add side glass and a removable back seat.

Completing the range later in 1957 was the brand-new station wagon (known at the time as the "Station Sedan"), available in Standard or Special levels of trim. As good on a building site as it was on a weekend trip to the beach, the wagon was arguably the best compromise for the multitude of single-car families that made up the bulk of the population, and it boosted GM's market share to just under 50 percent of Australian car purchases, with Holdens accounting for 42.7 percent of that (compared to 33.8 percent the previous year).

The FE ute was even more devastating to Holden's rivals, taking Holden's share of the ute market from 36.3 percent in 1956 to 50.8 percent in 1957.

The price had risen to £1,142, but increases in the average worker's earning power meant that wasn't far shy of $45,000 in 2023 money, so even with the extra kit, in real terms the price had barely moved. Today it's easy to be cynical and wonder why anyone would pay so much for such an unimpressive machine, but it's important to remember that in 1956, this was a lot of car for the money. If you couldn't find a place on Holden's waiting list (and couldn't afford a Yank tank...), your only other option was a British misery box: the Austin A40, four-cylinder Vauxhall Wyvern and six-cylinder Velox, and the Standard Vanguard (named for HMS Vanguard – military names carried a lot of weight in those days) were all fairly popular, but all struggled to cope with Australia's heat and rough roads. Only the Volkswagen Beetle and Peugeot 403 rivalled the Holden for rugged reliability, and those had their own problems (the Beetle was too small to be a serious family car, while the 403 was a rival for the Holden only until you hooked up a caravan or trailer). Ford's entry-level offerings included slop like the pre-war A493A Anglia and 100E Prefect, assembled at Norlane in sedan, roadster and ute guises. Power, if you could call it that, came from a 1.2-litre side-valve four-pot producing just 27 kW. They weren't even competing in the same category as the Holden.

Simply put, there was nothing on the road in 1956 that looked this good, could take this much punishment, and yet retailed at such a low price. After selling "only" 290,000 cars in the previous eight years, Holden would manage to sell 155,161 FEs in its two years on the market (and it would've been more, if only they could've built more). And naturally, sales got another tickle when the FE was chosen to be the official relay escort vehicle for the biggest event of the year – the 1956 Olympic Games, held in the Victorian capital of Melbourne.

|

| Rex Solomon carrying the Olympic torch between Johns River Hall and Holey Flat Bridge, south of Kew, NSW. (Source: Midcoaststories) |