The winner was... Melbourne? Australia's most European city had won its bid to host the Games of the XVI Olympiad by just a single vote over Buenos Aires, and as the opening ceremony drew closer the IOC's confidence in Australia hadn't grown. Disputes between state and federal governments over questions of funding had set back construction timetables markedly, and when IOC president Avery Brundage visited the Victorian capital 18 months before the Games were due to open, he expressed publicly his doubts that the city would be ready in time. Nothing ever changes...

And yet Melbourne was ready in time, and they did us proud. And more Australians than ever were able to enjoy the Games thanks to a new invention that had just made it to our shores.

|

| It must be said, all Olympic posters of this era look remarkably fascist. |

The Box

From late 1956, in the corners of living rooms across the country, there was a strange new device. For years its place had been occupied by the Wireless, around which the family had gathered to hear news about the war. But this was the 1950s, not the 1940s, and the old had been supplanted by the new. This box was about waist-high, shrouded in wood panelling – a real piece of furniture, in fact – and on the front, where for years had been only the tuner dial and AM/FM selector, there was a small glass screen. Television had come to Australia.

|

| AWA TV manufactured in Australia in 1956. The Old Fart tells me his first TV was an AWA (Source: Powerhouse Collection) |

Labor PM Ben Chifley had announced a government-backed foray into television immediately after the war, but his party had been booted from office before anything could come of it, leaving the idea to the tender mercies of Robert Menzies. Uneasy about the possible impact on society, Menzies did what conservatives always do, and stood athwart history yelling stop. He said to a visiting member of the BBC in 1952: "I hope this thing will not come to Australia in my term of office."

Given the sheer length of his term of office however, there was no avoiding it, and Menzies was forced to set up a royal commission into the idea in 1953. The commission recommended that the Television and Broadcasting Act 1942 be amended to allow commercial TV stations, operating along lines similar to those developed for radio. Naturally, the ideal deadline to have the network in place would be the upcoming Olympic Games in Melbourne: To broadcast the Games live around the world? That would be a real coup!

The first four commercial broadcast licences were handed out in 1955, all going to established newspaper firms. Channel Seven in Sydney went to a subsidiary of Fairfax (which owned the Sydney Morning Herald), while Channel Nine Sydney went to Frank Packer's The Daily Telegraph. Channel Seven Melbourne meanwhile was awarded to The Herald & Weekly Times Ltd, owners of The Herald and The Sun, while Channel Nine Melbourne went to a consortium that included The Argus and The Age. In effect, each major city got three channels – Channel Seven, Channel Nine and the ABC – and it would take time for TV to penetrate to more remote areas. Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia would have to wait until 1959, while Tasmania would not join in until 1960 (and as late as the early '80s, a cousin of mine quipped about our rural town having "compulsory television", since we only had two channels – Seven or the ABC – and you couldn't watch the ABC, because it was just news).

TCN 9 Sydney produced their first official broadcast on 16 September 1956, and audiences tuned in to see Bruce Gyngell, immaculately dressed in a dinner suit, utter the immortal words, "Good evening, and welcome to television." HSV 7 Melbourne followed on 4 November, while the ABC began transmitting from Sydney the following day. The phenomenon delighted so much that sales of TV sets boomed, and The Women's Weekly offered advice on how to rearrange living rooms to accommodate this new accessory.

So, how much do you think a new TV cost in 1956? Well, thanks to Trove, we have a nice, detailed breakdown of the costs, and the numbers are startling. The Argus forecast that it was going to cost somewhere in the region of £213 total (that's $8,660 in 2024 money!), of which £175 ($7,115) was for the box itself. To that you could add between £10 and £35 ($400-$1,400) for installation and aerial, and an extra £20-25 ($800-$1,000) any time you needed to replace a worn-out tube (which were promised to last either 6 months or 1,000 hours. The Argus warned that they were expected to need, "eight maintenance calls a year", which some firms were selling like insurance – an £18 premium (i.e. $730) would cover you for the year). And after all that, you still had to fork out another £5/5s ($215) for a U.K.-style TV licence, which would be introduced on 1 January 1957 and remain until it was abolished in late 1974. (Why? Because the cost of sending inspectors around to check everyone's living rooms cost more in wages than they were making back in fines. Apparently, people would dodge the fee by sticking the TV itself in a cupboard and hiding the aerial up the chimney. So all those people who torrent their media? Nothing ever changes.)

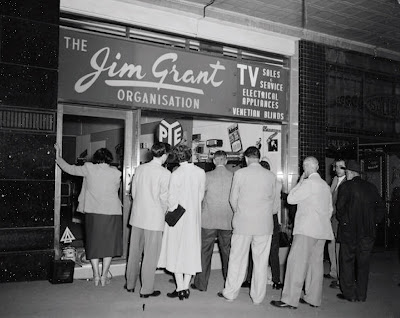

So like any new technology, not everyone could afford it, yet several publications predicted it would be quite fashionable to become the first household on your street to own one. Those who couldn't afford a TV of their own would often congregate outside shop windows to watch whatever was on. (Comment sections even contain evidence that some people considered this a date...!)

|

| Source: Melbourne Remember When on Facebook |

For many Australians, the Melbourne Olympics were their first taste of television ever, which is very fortunate given it almost didn't happen. All three stations – TCN 9 (Channel Nine), HSV 7 (Channel Seven) and ABN 2 (the ABC) – ended up televising the Games, but the issue of broadcast rights was not sorted out until a mere three days before the opening ceremony. The organisers claimed the rights had to be paid for, while the TV stations pushed hard for the Olympics to be classified as news, which they would be able to broadcast for free. Eventually it was agreed that the rights had to be paid for, and so Melbourne set an important precedent not only for subsequent games, but for televised sport in general.

Original Prankster

On 2 November, in the small Peloponnese town of Olympia, athlete Dionyssios Papathanassopoulos was handed a burning torch and began the first leg of the 1956 Olympic relay. He was the first of 350 Greek runners tasked with bringing the flame from Olympia to its immediate destination – slightly spoiling the romance, a Qantas airliner waiting on the tarmac in Athens. The logistics of getting to Australia meant that, of the more than twenty thousand kilometres the flame was about to travel, three-quarters of it would have to be done by air. As was the style at the time, Qantas flew the flame to Australia in a series of small hops, stopping over in Istanbul, Basrah, Karachi, Kolkata, Bangkok, Singapore and Jakarta. On 6 November, between Singapore and Jakarta, the Olympic flame crossed the equator and entered the southern hemisphere for the first time in history, before landing safely in the Northern Territory capital of Darwin. Here it was given to Tiwi basketball star Billy Larrakeyah for the short run to yet another waiting aircraft, this one an RAAF bomber.

The bomber crew brought the flame to the Queensland town of Cairns, where the relay proper began. The first runner was Con Verevis, a second-gen Australian of Greek parentage, a nod to the origin of the Games. He passed it to Anthony Mark, another well-known Indigenous sportsman from the Kowanyama community in western Cape York. The event was run with military precision, each man (and they were all men) required to complete his mile in under 6 minutes (necessary as the hexamine tablet used as fuel had only 15 minutes of life in it). Runners for the Kew-Burrell Creek section, for example, trained three nights a week at Taree Park (Johnny Martin Oval), carrying a dummy torch of the same weight as the real thing. "Some remember training in bare feet, while others tell of burning eyebrows and hair," Russell Saunders remembered for the Manning River Times. "It had to be held away from the body otherwise the sparks burnt the arm and clothing. Moreover, if you held it in front, smoke fumes billowed straight into your mouth!"

|

| Melbourne Olympic torch, minus its steel burner. (Source: City of Melbourne Collection) |

The torches themselves had been designed by architect Ralph Lavers and, true to Australiana of this period, were essentially a copy of the ones created for London 1948. Unlike the modern day, where manufacturing as many torches as there are torchbearers is a trivial matter, there were only 110 Melbourne torches made, so each had to be reused many times over. As the runners finished their leg, they handed the spent torch to an attendant in the support truck (supplied by GM-H, naturally), who removed the spent fuel cannister, gave it a quick clean and refuelled it ready for its next use. For what it's worth, Holden had recognised the promotional opportunity and provided five new FEs to be used as support vehicles: Holden dealers along the route refuelled, serviced and cleaned them.

Day and night, the flame made its way down the east coast, its bearers menaced by heat and soaking rains, and one torch actually broke when it fell to the ground in Lismore. But the defining event of the relay didn't come until the flame reached Sydney on the morning of 18 November.

Here waited the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Pat Hills, who was due to receive the flame from cross-country champion Harry Dillon. After receiving the flame, Hills was to make a quick speech and then pass it on to another runner, Bert Button, to resume its journey to Melbourne. A crowd of 30,000 had lined the streets to witness the event, with the usual battery of photographers and journalists stood at the ready to record this moment in history.

Then at 9:30am a young man appeared, dressed in grey trousers and a white shirt rather than the official runner's gear, but he was carrying a torch. The crowd began to cheer: the boys in blue shepherded him toward the Lord Mayor and, although taken by surprise at the lad's early arrival, Hills accepted the torch and went straight to the podium to begin his speech.

It took Hills quite a while to realise what he'd actually been handed: by some accounts, he didn't notice until an aide stepped forward and whispered in his ear. To the horror of the organisers, what the Lord Mayor of Sydney was holding was actually a common chair leg, painted silver, with a plum jam tin on top! The flame was burning nothing more noble than a pair of underwear soaked in kerosene. This "Olympic torch" was a forgery, the young torchbearer an imposter. The mayor looked around for the culprit, but he'd already melted back into the crowd and disappeared.

|

| Believed to be the only surviving photo of the incident. |

To his credit, Hills regained his composure swiftly. "That was a trial run," he said. "Our friends from the university think things like this are funny. It was a hoax by somebody. I hope you are enjoying the joke." The crowd was not enjoying the joke, in fact, and they became so confused and unruly that the police escort had to clear a path for the real Harry Dillon a few minutes later.

The culprit turned out to be one Barry Larkin, a veterinary student from St. Johns College at Sydney University. He and his mates had dreamed up the prank as a protest against the concept of the torch relay itself, which had been invented by the Nazis for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Larkin himself was never meant to be the torchbearer, the original plan giving that job to another student dressed in a white shirt and shorts like the real runners (another student had dressed in an RAAF Reserve uniform to act as a fake military escort). When this other student had stepped into the street and begun running toward the venue, he elicited a few chortles from the crowd, but then he'd waved his arm a tad too dramatically and flung the burning undies out of their jam tin and onto the ground. Panicking he'd fled, forcing another of the pranksters to retrieve the device and hand it to Larkin, who was sent on his way with a firm boot to the rump.

Few people knew what Harry Dillon looked like, so when a young bloke had appeared carrying a burning torch, everyone had just assumed he was legit. Larkin later recalled in an interview:

The noise was quite staggering. There were flashes of photography. I felt very strange because I knew I was carrying a fake torch. The only thing I could think about was what do I do when I got there. I was helped by Pat Hills. I just turned around and walked back down the steps, through the crowd and onto a tram and back to college.

Larkin was never charged, and indeed remained largely unidentified until the late '90s. When he fronted for an exam the following morning, his fellow students gave him a standing ovation and, although he failed the exam ("That's another story..."), he eventually completed his studies and went on to have a successful career as a veterinary surgeon. The fake torch ended up in the hands of John Lawler, a man who'd been travelling with the relay in a car. He stored it under his bed for several years until, eventually, it was thrown away by his mother while she was tidying his house. Even so, the event had caused quite a stir: The Sydney Morning Herald said it, "set a new standard for pranks", while London's The Independent called it, "the greatest hoax in Olympic history". Personally, I'd say it bears mentioning in the same breath as, say, the Chaser boys getting a fake motorcade into APEC summit. Nothing. New. Under. The Sun.

Let the Games Begin

The main venue for the Games was the storied Melbourne Cricket Ground – already more than a century old and recently upgraded, with the Northern or Olympic Stand built to replace the old Grandstand, making it one of the greatest sporting venues in the world. 103,000 people piled in for the opening ceremony, bearing witness to the arrival of guests from a dizzying array of countries. As the hosts, Australia had entered the second-largest team in the Games, with 294 athletes ready to contest almost every event – almost as many athletes as we'd sent to the previous twelve Games combined, in fact. Only the United States had brought a bigger team than us, with 297, and we outnumbered even the 272 of their arch-rivals, the Soviet Union. At the other end of the scale, the prize for the smallest Olympic team was probably a three-way tie between Iceland, Hong Kong, and North Borneo, who'd sent just two athletes each (which makes it remarkable that Iceland would leave with a silver medal in the men's triple jump). North Borneo were in fact making their only Olympic appearance, as come 1963 they would be subsumed into the new state of Malaysia, while also on their first Olympics were tiny Fiji (with a proud team of four), and Liberia. Afghanistan meanwhile had sent twelve athletes, all of them part of a single field hockey team. Overall, there were more than 3,300 athletes marching in the opening ceremony, representing a globe-spanning 67 countries.

It could've been more, but nine teams had axes to grind and chose to stay home instead. Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon and Cambodia all boycotted in protest of the Suez Crisis (in which Australia had admittedly been quite complicit), while the Netherlands had managed to talk Spain, Liechtenstein and Switzerland into joining a boycott over the ongoing Soviet invasion of Hungary (although, in deference to their concerns, the Soviet team joined a number of other countries in competing under the Olympic flag rather than the hammer & sickle). Mao's mainland China, meanwhile, chose to withdraw after a dispute over whether it was they or Taiwan who had the right to compete as the "real" China. It was a lot of bad blood for what was supposed to be "the Friendly Games", and although it is true that athletes from both East and West had come together to compete as a single unified Germany, that too would be going away once the Berlin Wall nonsense started in a few years' time.

The Olympic flame was carried into the stadium by a 19-year-old Ron Clarke (future Olympic bronze medallist, world record holder and Gold Coast mayor), who bore it aloft in a special, more ornate version of the Olympic torch. The flame itself was similarly unique as, worried it might not "read" on those tiny suburban TV screens, the organisers had added a touch of magnesium to the burner to really make it pop. Clarke completed his lap of honour, lit the big cauldron that marked the formal start of the Games, and then discovered he'd actually been quite badly burned, with several holes singed in his t-shirt and nasty burns around his right arm and wrist. He remained sanguine, telling the Sydney Morning Herald: "It was terrific being out there. I did not feel the burns at all until afterwards."

And with that, the games of the XVI Olympiad officially began. You can watch the official film here, either in a single movie-length feature or as a series of 20-minute vignettes.

|

| Jesse Owens, now middle-aged, still much fitter than you or me. (Source: Official Olympic film.) |

The guest of honour (in a sense) was the legend himself, Jesse Owens. Twenty years before, in Berlin, Owens had made a mockery of the Nazi doctrine of racial supremacy by personally winning four gold medals (in the 100m sprint, long jump, 200m sprint and 4x100m relay – the first three on successive days. And yet, that was arguably only the the second most impressive feat of his athletic career...!). Indeed, his long jump gold had been won without breaking his own World Record, which in 1956 was still unbeaten. What's even more amazing is that it remained unbeaten when the Games were over: compatriot Gregory Bell took home the gold after a jump of 7.83 metres, but Owens' 8.13-metre record still loomed over it all. Not until Rome 1960 would Owens see his last record fall.

Watching it back, it's clear some things have changed significantly, while some have stayed remarkably the same. An event that hasn't changed much is your bog-standard 100 metre sprint. In Paris 2024, of course, it was won by Noah Lyles (and his tiara...) in a blistering 9.79 seconds. In Melbourne, it was won by the Texan, Bobby Morrow, in 10.5 seconds. That's... not as much improvement as I'd have expected, given seven decades of growing professionalisation, better nutrition, improvements in training, etc. I know the margins aren't going to be huge on such a short event, but it surprised me all the same. Almost like Mother Nature had already run a several-million-year programme to optimise the human beast for running...

|

| Dumas certainly had style. (Source: The Geelong Advertiser) |

The high jump, on the other hand, looked very different. Today we're used to seeing jumpers fling themselves over backwards, but in 1956 things weren't done that way. Everyone ran at the bar and leapt over it like primary schoolers at their first sports day, treating it like nothing more than an unusually high hurdle. The reason is that the backwards technique was yet to be popularised by Dick Fosbury, who would use it to win a gold in Mexico City 1968. Since then the technique has been known as the Fosbury Flop, but you'll note the operative word in the previous sentence was "popularised", not "invented". The move was known before 1968, but almost nobody used it because – as you'll see if you watch the footage – the landing pad back then wasn't a nice, thick, cushioning foam mattress, but a simple pile of sand. Doing the Fosbury Flop into a sandpit would probably be a short cut to a broken neck, so jumpers were restricted to methods that allowed them to land safely on their own two feet. In the end, the event came down to a contest between Australian wool grazier Charles "Chilla" Porter, and America's Charles Dumas. The bar eventually went too high for Chilla, who was unable to clear anything higher than 2.10 metres. Dumas managed a 2.12 and so took home the gold.

The darling of the Games was our "Golden Girl", Betty Cuthbert, who won both the women's 100m and 200m sprints before anchoring the 4x100m relay team. When it was all over, she returned to her ordinary suburban home with three gold medals and a new status as Australia's Sweetheart. In effect, Betty Cuthbert ran so that Cathy Freeman could... run even faster, I guess? Anyway, the senior member of the women's team, Shirley Strickland, managed two gold medals in her final Olympics, winning the 80m hurdles (reducing the World Record to 10.7 seconds along the way) and teaming up with Cuthbert for the 4x100m relay (again resetting the World Record, this time to 44.5 seconds) – ending her career with a formidable collection of three gold, one silver and three bronze medals.

|

| Busting a gut: Cuthbert claims some more precious metal. (Source: The West Australian) |

But the track and field medals were just a bonus. The real business was in the pool where, establishing a trend the world would recognise in coming decades, the Australians absolutely cleaned up. The venue for these events was Melbourne's Swimming and Diving Stadium – what is now known as AIA Vitality Centre – and it would see the Olympic debut of one of the sport's greatest exponents, Murray Rose, and a straight-up household name, one Dawn Fraser. Dame Dawn won gold in the 100m freestyle and 4x100m freestyle, plus a silver in the 400m freestyle, while Rose claimed a trio of golds in the 400m freestyle, 1,500m freestyle and 4x200m freestyle (not for nothing do they call it the Australian Crawl). Adding to the medal tally was David Theile, winner of the 100m backstroke; Jon Henricks, winner of the 100m freestyle; and Lorraine Crapp, who managed a 400m freestyle and 4x100m freestyle relay gold medal double (Though she never escaped the jokes: "Why does Dawn Fraser swim so fast?" my Pop never failed to ask. "Because she saw Lorraine Crapp in the pool!"). When everyone towelled off, Australia had walked off with 8 of a possible 13 gold medals in swimming – more than half of our final Olympic total.

|

| Rose Gold. And at just 17, he had plenty left in the tank, too. (Source: Nine.com.au) |

But of course, the biggest talking point of the Games was another swimming event entirely...

Concerning Hungarians

Though it might be over-generalising, I think it's fair to say the Hungarians are a very independent people. They'd spent the 19th Century levering themselves out of the decrepit Habsburg Empire, a process that had only been accelerated by the outbreak of the First World War, which for complicated reasons had then led to Hungary siding with the Nazis under their own fascist dictator, "Admiral" Miklós Horthy (and if you're wondering why I'm putting scare quotes around the word "admiral", well, have a quick look at Hungary on a map). In the immediate post-war world, however, their fascist past didn't do much to endear them to their new Soviet overlords, who after everything they'd been through were determined to keep Germany weak and divided, with a series of nice, compliant buffer states between themselves and Berlin.

By 1956 the war was over a decade in the past, people were beginning to move on with their lives, and – probably the most important point – Stalin himself was now dead (they made a whole movie about it). Filling his shoes was a new guy, Nikita Khrushchev, a peasant's peasant who was barely three years into his tenure as General Secretary of the Communist Party. As a result, 1956 saw a wave of unrest on the far side of the Iron Curtain. Protests in Poland, for example, managed to avoid civil war, and in fact resulted in concessions even as Soviet rule was reaffirmed, so a number of Hungarians felt the time might be right to tug at their chains and see how loose they might be.

They were mistaken. Khrushchev's response would've made Stalin proud, rolling in 30,000 Soviet troops and over a thousand tanks, crushing the uprising within two weeks. By the time the dust settled, the Soviet Union was firmly back in the driver's seat, and at least 2,500 Hungarians had been killed.

Busy training outside Budapest when the revolution began, the reigning Olympic champions heard the gunshots and saw the smoke rising above the city, but were kept in the dark about the true scale of what was happening. To keep them out of harm's way, they were moved to allied Czechoslovakia before making the journey to Australia, only discovering what had truly taken place after they arrived in Melbourne. Finding themselves matched against the Soviet team in the semi-final match on 6 December, the Hungarian team saw a chance to regain some national pride.

The atmosphere in the Swimming and Diving Centre was tense from the beginning. The Hungarians came in planning to provoke their opponents by insulting them in Russian. Said Hungarian star Ervin Zádor: "We had decided to try and make the Russians angry to distract them."

It worked. With the score at 2-0, Soviet player Boris Markarov punched Hungarian Antal Bolvári, triggering a series of brawls up and down the pool that took the referees some time to bring under control. If that had been the end of it, this still would've been a match for the record books, but the worst was yet to come.

The Hungarians were leading 4-0 when, in the final quarter, Valentin Prokopov suddenly planted one right on Ervin Zádor's face. The blow was so hard it drew blood, and images of Zádor beside the pool, blood streaming down his face, earned the game the moniker, "the Blood in the Water match". At the sight, the 5,000-strong crowd – most of them Hungarian expats – lost their minds and rushed poolside, aiming to get their hands on the Soviet team as soon as possible. The Victorian police were forced to intervene, and the officials called time on the game to give all athletes the chance to leave the venue alive. Since they'd been leading when the whistle blew, the Hungarians were declared the winners.

|

| Zádor on his way to the infirmary. (Source: KGOU) |

Luckily, even without the wounded Zádor, the Hungarians prevailed 2-1 in the final against Yugoslavia, and so earned gold for their second Olympics in a row. But it was a bittersweet victory. After quiet, intense discussions behind the scenes, 46 Hungarian athletes and coaches refused to return to their homeland, seeking political asylum in the west instead. At first they were spurned, but then Sports Illustrated got involved and convinced the U.S. to offer asylum to 34 of them, including water polo team members Miklós Martin, Antal Bolvári and, yes, Ervin Zádor. Another dozen went to other western countries, with featherweight wrestler Bálint Galántai even finding a home here in Australia.

The Final Accounting

The Soviets had the last laugh, though. They emerged from the Games with a grand total of 98 medals – 37 gold, 29 silver and 32 bronze – the highest medal count of any country in the world, including the United States' 74. It might not be official, but to a certain kind of person the country at the top of the medal table will always be considered to've "won" the Olympics, and in 1956 that was the United Soviet Socialist Republics. Australia was first behind the ideological titans, winning 35 medals in total (13 gold, 8 silver and 14 bronze)... although just behind us was none other than the Hungarian People's Republic, with 26.

The hostility of that water polo match was still on everyone's mind as the closing ceremony approached. The TV news at night was full of Cold War tensions, and after the ugliness of the Sèvres agreement, the Suez Crisis, Hungarian Revolution and the most violent water polo match of all time... well, it all rather undercut the idea that this was The Friendly Games.

Seeking a more hopeful note to end on, organising committee chair Kent Hughes gave the nod to a suggestion made by a 17-year-old Chinese-Australian named John Ian Wing, changing the format of the closing ceremony substantially. Rather than marching as separate teams behind their respective flags, Wing suggested that athletes be allowed to march freely as individuals, mixing and mingling as equal citizens of a single, unified world. Once again Melbourne had established a precedent, for not only did the organising committee adopt Wing’s suggestion, it has been the tradition at every Olympic Games since. Wing said:

During the march there will be only one nation. War, politics and nationality will be forgotten. What more could anyone want, if the whole world could be made as one nation?

What indeed.