We won the Wellington 500 two years in a row and after the first year I got out of the car and asked Peter why we had waited 20 years to pair up. – Allan Moffat, AMC #78After a character-building 1986, the Mobil Holden Dealer Team came roaring out of the blocks in 1987 with victory in the Nissan Mobil 500 on the streets of Wellington. It was the second time the pairing of Peter Brock and Allan Moffat had won the New Zealand race in as many years, and even better, 2nd place had gone to their teammates John Harvey and Neal Lowe, marking HDT's first 1-2 finish since the Big Bangers at Bathurst in 1984. Unfortunately, history would record that it was also HDT's final win as the factory team.

|

| Source |

The Streets of Wellington

Although only three years old, by 1987 the Wellington 500 had come along by leaps and bounds to become the second-biggest touring car race in the region, attracting a sizeable contingent of European cars and drivers (who certainly didn't show up for Sandown). As such, this year it had a joint Australian/New Zealand commentary team (including aspiring race driver, Neil Crompton, and full-time Peter Griffon cosplayer, Mike Raymond), to be carried live and in full by TVNZ and Australia's Channel Seven. All four hours of it, live.

The race's growing stature also shed some light on the mystery of last year's "South Pacific Touring Car Championship." This it seemed had been organised as a trans-Tasman grudge match to encourage more of the Aussie teams to make the trip to East Bondi, and maybe take part in the Wellington race while they were over there. The calendar apparently looked something like this:

19.10.86 – Calder Park, Aus.By the time the tour made it across the Tasman it had been branded the Simpson Appliances South Pacific Touring Car Championship, and the NZ rounds had virtually replaced the New Zealand national championship (which also counted the Nissan Mobil double-header at Wellington and Pukekohe). However, the series was a complete failure as none of the Kiwi teams bothered attending the Australian rounds, and none of the Australians bothered with the New Zealand rounds either. The title of South Pacific Touring Car Champion went to '86 Bathurst winner Allan Grice, who did it simply by earning points in every round (driving both Commodores and, intriguingly, Nissan Skylines – an early hint of how Gricey would be spending 1988). Glen McIntyre did better in the NZ leg of the tour, and so was crowned New Zealand champion.

26.10.86 – Streets of Adelaide, Aus.

30.11.86 – Manfeild Autocourse, NZ.

07.12.86 – Bay Park Raceway, NZ.

14.12.86 – Pukekohe Park, NZ.

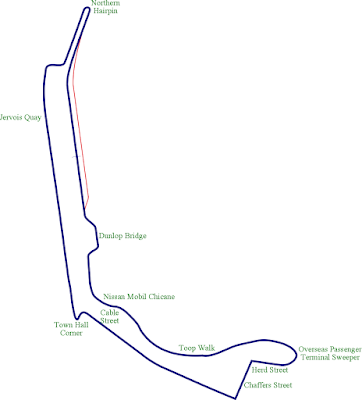

The irony was that although the South Pacific series was a failure, the race it was meant to prop up was a runaway success. They were now calling it "the Monaco of the South Pacific," which was a bit rich when the Kiwis still did nothing to conceal its port-city origins. It was more like Long Beach, quite an eyesore in places, but the hills rising behind the city and the crystalline waters of the Harbour went a long way toward making up for it. The circuit had been lengthened slightly this year, probably to comply with the FIA minimum for World Championship events, by extending the run along Cable Street to the Hurd Street Loop (unfortunately, Wellington has since built things like the Museum of New Zealand in the way, so it's impossible to follow the complete layout today). It was still quite a slow circuit, with a mixture of very slow and very fast corners lined by the ever-present Armco, and as a public road the surface was still very bumpy (with a particularly vicious bump right on the entry to the Northern Hairpin – several of the cars were lifting their front wheels off the ground over that one).

|

| Source: Wikipedia |

What's also sometimes forgotten is that there were two Wellington 500s in 1987, one in January and one in October. The Wellington race had joined the World Touring Car Championship calendar, and to make the logistics suit the European teams they had to schedule it right alongside Bathurst and Mt Fuji. That meant moving the race to late October, which left the Strathmore Group, the race's organisers, with a quandary – do they hold off on their January date and go nearly two years without holding a race? Or do they give in to their blue balls and have two races in the same year? With the race now profitable, that was an easy decision.

It's the January event that's remembered here in Australia, mostly because it was won by an Australian car and Australian drivers. And because those drivers were Peter Brock and Allan Moffat, with twelve Bathurst victories between them, we tend to assume it was all pretty inevitable. It's only when you watch the full race on YouTube that you realise it wasn't like that at all. The track was brutal, the opposition was impressive and the luck was entirely reserved for one car and two drivers. This was a day when every team seemed cursed – except one.

Hot & Hard: Race Day

As per FIA regulations, the race was set for 500km or 4 hours, whichever came first. It was a race of high attrition, 42 cars taking the start and just 14 making it to the finish, the wicked Armco barriers and unexpectedly high temperatures taking a heavy toll on stressed cars and wilting drivers. George Fury, lead driver for the Peter Jackson Nissan team owned by Fred Gibson, had put his factory(-ish) Skyline on pole with a time of 1:33.93, according to the TV commentary at least (TouringCarRacing.net lists different times, but their info is often unreliable, qualifying times not corresponding to grid positions and whatnot. So we'll go with what the TV says). Peter Brock had qualified in P2 with a time of 1:34.18, only a quarter of a second slower: for comparison, a blink takes about a third of a second. That's pretty tight for cars from different manufacturers, with different engine configurations, on different tyres, and it must've pleased the sponsors no end: for the Nissan Mobil 500, the car on pole was a Nissan, and the car starting 2nd was backed by Mobil.

|

| Photo via The Roaring Season, which has to be one of the best, most informed and most civil online forums out there, even if they're only interested in New Zealand. Go check them out. |

The race began with a rolling start at 1:00pm, in preparation for the WTCC races coming up later in the year. This suited the turbo Skyline of Fury just fine. The Albury ewe farmer rocketed off into an early lead, chased hard by Armin Hahne in the #52 Jaguar XJS of Tom Walkinshaw Racing. This was actually the same car that had won Bathurst in 1985; after a gap year in 1986 while "Uncle Tom" had run his Rovers instead, they'd been brought out for one last dance in the Fuji 500. That should've been their last race, as their homologation papers ran out at the end of 1986, but the Strathmore Group proved so keen to have them in their race that they granted an extension and paid for the cars to be flown over to New Zealand instead. So Tom himself was driving the #51, with relief from his faithful lieutenant Win Percy, while #52 – the Bathurst winner – had been reunited with its driver Armin Hahne, with co-driving to come from New Zealand's 1967 F1 World Champion, Denny Hulme.

In the early laps, Hahne wasn't showing it much mercy, flogging the XJS for all it was worth to keep up with Fury – and Fury was vanishing into the distance nevertheless. The gap grew from 2 seconds, to 7, to 20, and then he was out of sight and gone. This was one of the great drives of all time, because we already know the DR30 was a nightmare to drive, twitchy and understeering going into a corner, prone to snap oversteer one the way out, and cursed with way, way more power than the primitive suspension and narrow tyres could really handle. The last place you'd want to drive it was a narrow, bumpy street circuit, where precision was everything and you had to time the arrival of the boost in all those slow corners – yet Fury made it look as docile as an MX-5. For an "amateur" driver, he really was absurdly talented.

I can't find out for certain, because Gibson Motorsport seems not to release chassis numbers much, but I'd put money on the car being the team's first DR30, as driven by Fury in the 1986 ATCC. They'd built a new car for Bathurst, and its stiffer rollcage design meant the setups Fury had developed didn't transfer across, and he was out-qualified and out-raced that year. It makes sense that they'd save their newer cars for the ATCC and risk the old one on a non-championship race like this, which would explain by George Fury was suddenly back on his game. But then again, apparently only two teams had tested over the off-season, and they were Gibson Motorsport and Perkins Engineering. Make of that what you will.

|

| Finally we can use this image in its proper context. |

Behind them, however, the carnage started as early as lap 3. Coming through the right-hand sweeper before the bridge, the driver of the #4 U-Bix Copiers Volvo, Gary Croft, touched a barrier and broke the centre-lock nut holding on his front wheel. In the ensuing crash he collected Graeme Bowkett in the #15 Nu-Look Windows Skyline. Wellington continued its vendetta against Bowkett and co-driver Kent Baigent: they'd won the race in '85 only to have it taken away from them by an official decision, then crashed out in the early laps in '86. Now history had repeated, and through no fault of their own. Bowkett's Skyline was left up against the Armco, pointing in the wrong direction looking like it had been punched on the nose, steam hissing from a cracked radiator. Croft was able to limp back to the pits and carry on, but for Bowkett and Baigent, the day was done. The marshals were left to dodge the traffic as they levered it up against the barrier, as far out of the way as the track would allow, leading the commentators to augur that when the Europeans came over later in the year, maybe they'd bring this innovation called a "Safety Car" with them!

The next green bottle to fall was Allan Grice, the hero of Bathurst '86. His #2 Canam Construction Commodore, a Roadways-built example he'd debuted at the Adelaide GP support race and since sold to co-driver Graeme Cameron, vanished from the TV coverage on lap 7 and wasn't noticed until we saw the car parked behind an advertising board, as if it was embarrassed. Gricey arrived back in the pits – on foot – to tell Neil Crompton:

Grice: Broke a tailshaft, right in the middle of the spline. The old story – we've never ever done that before, and it was a new one also.The next victim was Andrew Miedecke's #1 Sierra XR4 Ti, which was seen trundling down the back straight with a lot of smoke coming from the right-rear wheel arch. It was looking like it was make the pits under its own steam, but boy was it going to lose some time doing it, and the repairs looked extensive – the right-rear wheel was sticking out at the wrong angle. This car was Andy Rouse's 1985 BTCC championship-winner, which had been brought over for the '86 race by David Oxton and made its Australian debut at Surfers Paradise. It was now getting a bit long in the tooth and, being Andy Rouse's handiwork, had a long history of breakdowns. The car kept going, but it was in and out of the pits all afternoon, so it was never a threat again.

Crompo: Was it likely to've come out of the accident on the last day [of practice]?

Grice: I suppose you've gotta in the end put it down to that, you'll never ever know, but one of the two thumps it's taken has probably put some sort of a hairline crack in there I guess. But it hasn't happened to us before. It used to be our weak link, and like all weak links we fixed it up so well that we started to regard it as our strong point!

|

| Chasing Tony Longhurst's BMW 325i |

With the race now an hour old, fuel strategy started to become a factor. The notoriously thirsty Jags were likely to require three stops to make the full distance. The Commodores would need two, and the really efficient cars, like the BMWs, could probably do it with just one. The real wild card was Fury's Skyline, which was faster than a Jag, its tyres a little worse for wear, but showing no signs that it would run out of fuel anytime soon. Such a preposterously fast car couldn't possibly go the full four hours on just one stop, could it? Time would have to tell.

In the meantime the Jags were clearly running out of steam, and headed for the pits even earlier than their expected early stops, not for fuel, but for tyres. It seemed Tom Walkinshaw had been caught out by the weather: expecting more Kiwi chill and drizzle, Uncle Tom had fitted his cars with special kevlar-belted soft-compound Dunlops to give his big cats the spring they needed for the slippery streets (and fuelling the rumours that his Jaguars needed bespoke tyres for their modified wheel wells...). Instead, January 25 was a bright summer day, several of the European drivers were wilting in the heat (Tom himself was wearing a cool suit), and the big, one-and-a-half-tonne V12 Jags had completely worn out their special tyres. Coming in for fresh rubber and driver changes, the mechanics fitted harder compounds to compensate, but without the extra grip the Jaguars couldn't maintain their lap times. And then, when Denny Hulme got in for his stint, a problem with the right-front wheel gun meant he tried to set off before the wheel was properly affixed. They lifted the car again for another go and this time got it screwed on right, but the mistake cost him 15 valuable seconds. This sort of thing proved HDT and Gibson Motorsport wise in sticking to old-fashioned five-stud wheels – their wheels stayed on, and since refuelling was the thing that took the longest anyway, they didn't really lose any time in the pits.

Denny's misfortune promoted the train of Commodores behind him by one place each, although at the front George Fury was now 30 seconds in the lead and still running away. Ten minutes later however, on lap 47, Graeme Crosby pitted as well. It was perhaps a little early, but his car – an ex-HDT Commodore with a Les Small engine, dressed in the signage of Wang Computers – was right at the edge of its fuel window, so it didn't seem too suspicious. Maybe he'd just been running very hard? Then we realised co-driver Wayne Wilkinson was making no attempt to hop in. Instead the bonnet was lifted, and hearts sank.

Croz: We appear to have a fairly hot-running engine – the problem being that when you're following somebody really close, you've got no cooling because of the amount of air that they drag behind you [sic]. So it's impossible to follow real close, and the crash damage did we got [on Saturday] we think we might've blocked a bit of the filter, so that's really where we are.

Crompo: Perhaps loosened something up in the cooling system which has now floated back in and caused an overheating problem?

Croz: Oh that's too technical! We just don't have enough cooling going to the engine. Oil temperature's running about 145, which is about 20 to 25 too much. Water temperature's about a 120, which is about 20 too much, 25 too much.

|

| Again, photographed at Pukekohe the week after |

So that was it for the Wang car (...steady...). Mind you, at this point you wouldn't have picked Moffat and Brock to win it either. Starting from P2, Brocky had almost immediately dropped back behind Hahne's Jag, then the rival Commodores of Graeme Crosby and Larry Perkins – and then even his own teammate, John Harvey. This wasn't how Peter Brock won his races – Evan Green in particular liked to speak of the "Brock Crush," his habit of running hard in the first hour to make the bastards chase him, then backing off and letting them break down trying to catch up. It seemed impossible that his VK wouldn't be the fastest on the track, so seeing him falling back, the commentary team were forced to conclude that he had a problem.

In fact, as we found out an hour and twenty minutes into the race, Brock had simply been running to a predetermined plan. It's likely he knew the weight of the Commodore would eat his tyres if he wasn't careful, so he decided it was better to save the fireworks for later in the day, when the temperatures dropped off. Seeing the hares in his mirror – Crosby, Grice, Hahne – he probably decided it would be better to pull over and let them go than end up in their accidents. It was only when he pitted to refuel and hand over to Moffat that he learned there was still ample tread on his tyres, so he could've gone faster quite easily. Moffat no doubt filed that information away. The Commodore actually wasn't a bad bet for this sort of race: despite their weight and power, they actually handled quite well.

And then – just before the two-hour mark – George Fury finally made his scheduled pit stop as well. Four tyres were changed, fuel was sluiced in, and a 21-year-old Glenn Seton hopped in for his half of the race. And yet... the car didn't speed away. As the fuel went in, a mechanic sprayed the windscreen with cleaning agent, and then the bonnet was lifted and more mechanics peered in and started arguing with each other. Disaster.

Neil Crompton: As you can well see, the George Fury/Glenn Seton Nissan is in the pits and they've been in there so far for 55 seconds. They're working on the front of the car because it appears to be overheating quite a lot. As I look down the side of the car it's covered in glycol, which is the cooling fluid that's used on these cars to run them at very very cool temperatures – in the turbo areas of these cars they get up to something like 100,000rpm, and temperatures of 900 degrees C, so you can imagine that they really have to work at keeping them cool.Fury later told that the fan belt had broken around the back of the course, on the very lap he was scheduled to come in. Five minutes and 21 seconds in, and the crew admitted defeat, closed the bonnet and pushed the car around to the rear of the pits. Fury's magnificent drive had netted him nothing; Seton never even left his pit box. From a virtually certain win to a DNF in half a lap. It could be a cruel sport sometimes.

Andrew Bartley is at the front of the car, he's one of the top men in the team, and the rest of the Peter Jackson crew are working frantically. 1 minute and 27 seconds in the pits, and that will definitely mean they're going to drastically lose that lead they worked so hard for in the early laps.

Fred Gibson is walking up to the side of the car to have a word with Glenn Seton to keep him informed, because he will need to know what kind of problems the car has, and is now just mounting the drink bottle for Glenn. But this is a very long and slow stop for the Nissan, 1:51.

It's interesting that the car had no problems before they came to the pits and I just wonder whether when they lost momentum, they actually caused an overheating problem?

Just as I look under the front of the car, it appears as though the fan belt has flicked off. I don't know if that's absolutely true, but they're working frantically on it. 2 minutes and 15 seconds, and Crowe I should imagine [sic – it was still Jim Richards] has gone into the lead in car number 31, the driver who shared with Tony Longhurst in the 1986 event now leads the Nissan Mobil 500 around the streets of Wellington. They're still working on the front of the Nissan, 2 minutes and 35 seconds down. Fred Gibson peering in the front of the car, Bo Seton at the front of the car – he's the father of Glenn. Oh, this is a drastic stuff. George Fury's disgusted, he's walked away to the back of the pit area, and look at this, as the car now gushes steam out of the front of the radiator...

Fury's retirement blew the game wide open. Now in the lead was Jim Richards in the #31 Archibalds BMW 635 CSi, whose black and gold paint scheme gave it away as an ex-JPS Team car. Looking through the back window, the distinctive X-shaped roll cage marked it out as the third of the three 635s built by Frank Gardner's crew in their Terrey Hills workshop in Sydney (the first two had a single diagononal bar in this position). This was the car in which Richards had won the Lusty-Allison Winton Roundup last year, but which had just been sold to his Wellington co-driver, New Zealand's Trevor Crowe. Since the John Player team were busy screwing together brand-new cars for 1987, clearing workshop space was a priority.

But although he had a nice gap over 2nd place – the #10 Sunday Star Sierra of Neville Crichton, an ex-Eggenberger car which had been co-driver Steve Soper's ride for the second half of the '86 ETCC – Gentleman Jim was actually out of sequence, due to make a pit stop very soon. A flurry of pit action saw Uncle Tom get back in the #51 Jag, and then Richards pulled in and handed the Archibalds BMW over to Trevor Crowe for the 2-hour run to the flag. That promoted Steve Soper to the race lead, although Allan Moffat was right behind him and disputing it.

But before they sorted anything out, the race took another casualty in the form of David "Skippy" Parsons, who'd taken over the #11 Enzed Commodore on behalf of Larry Perkins. This car was almost certainly PE 002, the second Commodore ever built by Larry under his own Perkins Engineering banner, on the logic that PE 001 had been sold after the GP support race the previous year. Interestingly, both Perkins and Parsons (by day a Tasmanian dairy farmer) had once been members of HDT, but they were going to be in no position to threaten their former colleagues today. Parsons came into pit lane with panel damage, two flat tyres and far too much front toe-in, suggesting something had bent in the steering.

Parsons: Just a lot of rubbish and what-have-you, and just slipped and just clipped the Armco by about a couple of inches on one side. Just beamed me straight into the other side. Couldn't do anything about it.At the time Perkins was just another owner-driver, far from a wealthy man – this car in fact belonged to Colin Giltrap, a bigwhig NZ car dealer who'd previously backed his foray to Europe and Formula 1 in the 1970s. Perkins had settled on the racing number 11 on the logic that in the absence of the cheapest and easiest number to paint – the #1, reserved for the reigning champion – the next easiest and cheapest must be a pair of ones! That kind of thrift was second nature to him, so he could be forgiven for walking slowly around the car with his hands in his pockets, surveying the damage with an expression that would've curdled new milk.

Soper's time in the lead didn't last much longer. Soon the #10 Sierra was back in the pits, collapsed on the left-hand side with a front wheel missing. The rush to fit a replacement didn’t go as planned, as the thread had probably been damaged as the wheel was wrenched free (if it hadn’t been the source of the problem in the first place). Either way, they had to make multiple attempts to get the wheel on, and the car spent four minutes sitting still. Its race too was over.

So, with 2½ hours and 84 laps gone, it was now a straight fight between the Brock/Moffat Commodore and the Richards/Crowe BMW, the only cars still on the lead lap. The sinister black Beamer was 47.85 seconds down, it was true, but the Commodore still had to make another pit stop. HDT could be expected to change the tyres and top up the tanks in less than 45 seconds, so it was the gap that mattered – and Allan Moffat now had the hammer down.

As the laps ticked away the HDT crew chewed their nails nervously, made ready to bring Moffat in and put the boss back in the car for the run to the flag, mentally rehearsed to do even better than the 35-second stop they'd managed the first time around, and then... The last green bottle fell, and it was Trevor Crowe, who failed to come past the start/finish line on lap 98.

Crompo: Trevor, what happened?The clutch was indeed a suspect part in the 635, built for Europe's rolling starts; the combination of Wellington's slow corners, the car's tall gearing and the unexpected heat of January had just proved more than it could take. Frank Gardner and Jim Richards could only hope their new car was built to take a bit more abuse.

Crowe: We're not sure, we think it's the clutch, it could be a halfshaft universal. It's just lost all drive, won't go in any of the gears. Tried them all. Had no warning at all. The car really did feel good before that, you know it was running perfectly, we still had a lot of brakes, I was just conserving tyres with full tanks, waiting for a bit of a burst later on – once the petrol level goes down, you can give it a bit more. So, cruising along, it’s just one of those things. Second year in a row!

Crompo: You're the unluckiest driver of the last two Nissan Mobil 500s, recalling last year when you and Tony [Longhurst] pushed the leaders along. In fact it was the same team you were pushing! And then again you get three-quarters of the way this year and ditch it at the last moment?

Crowe: Yeah well, it's disappointing, but it is motor racing – it's an old phrase, but it's quite right. You've really gotta be there at the finish. It's been a bit of a problem, the BMWs with the clutch is... you know Jim lost one in Adelaide in a good position, it's just something that seems to go on them. But, you know, we've enjoyed our weekend and look forward to next week.

Crompo: You gave it your best shot. Good luck next week at Pukekohe.

The loss of Richards and Crowe was a huge bone to HDT, but that didn't mean the pressure was off completely. After a lacklustre middle of the race, the Jags suddenly came roaring back, Walkinshaw pitting shortly before 4:00pm to put Win Percy back in for one last kamikaze stint. They weren't winning, and no matter what happened this was the XJS's last race, so there was absolutely nothing to be lost if they stuck it in the wall. Percy did up his belts, slammed shut the door and took off to drive the stint of his life.

Their timing however cost Hahne dearly. Hahne had not been kind to his Pussy, pushing his to the ragged edge, locking up under brakes and getting sideways onto the bridge – he had worn his rear tyres right out. Indeed, it emerged later that he had a slow puncture in the left-rear. He'd asked to pit, but was rebuffed because at that moment Walkinshaw was in the box, leaving him to complete another lap with the tyre going down. It was a lap too far: the next time around, Hahne lost it again at the Bridge and ended up facing the wrong way – the first we knew was the vision of the marshals pushing the car backwards, putting it alongside the Bowkett Skyline that had been there since lap 3. Tom looked angsty, hovering around the pits with his race suit undone for ventilation, showing off his boxer's physique, but he didn't say a word. Not to worry – with the WTCC coming up, the rumours were already swirling that he’d be running Holden Commodores. There’d been a number of quiet visits to Melbourne, for one thing; for another, it was understood by some that he’d already taken delivery of a planeload of parts...

Neal Lowe had spent the last hour or so trying to find a way past Glen McIntyre in the #7 State Coal BMW. This car was being leased from Charlie O'Brien, which means it was probably his Bumper 2 Bumper car from 1986, which would make it the JPS Team's second car from 1985. It was being leased to the State Coal team (which, interestingly, had the same livery as the #8 Goldair car even though it had a different sponsor, implying they were a team. The Goldair entry however was the ex-Frank Sytner car from 1985. One wonders if it had power steering yet...). Although the fourth of HDT's four drivers – co-driver to their second car – it was Lowe who managed to find a way past McIntyre after almost an hour of on-track brawling. Neither had been silly enough to risk a touch with the wall for 3rd place.

Crowe's retirement turned 3rd place into 2nd, putting HDT into an enviable 1-2 position. But unfortunately, as with the Moffat/Crowe duel, the Commodore had to stop again, and the BMW didn't. Lowe lost the place when he brought the #3 back to the pits for its final fuel and driver change. Prime driver John "Slug" Harvey jumped back in and did up his belts in the knowledge that it was all up to him to make up the 14-second deficit before the clock ran out.

In fact, with nearly an hour in hand, it turned out that yes he could – Slug made his move on the back straight with half an hour to go, outbraking McIntyre into the tight chicane behind the houses. Mobil HDT were too wise to count their chickens, but it was nice to have nothing left to overcome but the clock.

Or so they thought – like lightning out of a blue sky, suddenly the last surviving Jaguar was back. Win Percy was under orders to fang it, because if the Jaguars couldn't win their final race, they should at least have the fastest lap. Thing was, he was so fast that with fifteen minutes to go, Percy came upon John Harvey and started harassing him for position! Coming out of the Northern Hairpin he was in Slug’s door mirrors, ducking and diving for a way past, and through the tight funnel onto Jervois Quay both got baulked by an Alfa Romeo GTV6. That set them up for a straight drag down the long back straight, and sure enough, Percy's V12 won it, pulling up for the narrow kink with P2 in his back pocket.

Of course Brock was 2 minutes and 10 seconds up the road, so P2 was probably as good as he was going to do today, but it was still a heroic effort. But you can probably guess what happened next. Yep, just a lap later, the big cat slowed with a problem, as we were treated to the vision of Percy touring back to the pits with the normally-lithe XJS sounding like a cement mixer. This was not a small failure. The Walkinshaw team had given it everything, but in the end, it just wasn't enough. Percy got a round of applause as he alighted from the car anyway, and disappeared out the back to find himself a well-earned drink.

That might've been the end of the contest, but it wasn't quite the end of the race. Like Odysseus, HDT had worn through every other team's life strands, and finally clear the pit crew hung out the sign for a formation finish. All pretty routine, except that in a bizarre final act the Mobil cars toured past the finish line in a formation the Roulettes would've been proud of... and the chequered flag wasn't shown to them. They'd have to complete another lap.

That wouldn't have been too weird, except that while the HDT cars had been slowing down for their formation finish, Glen McIntyre had caught back up. Sitting behind a pair of slow-moving Mobil Commodores, McIntyre too had missed that the chequered flag hadn't yet flown, and so missed out on a chance to spoil HDT's party. So it was that Peter Brock won the race, then realised he hadn't, and committed to another lap with Slug by his side, shadowed by a McIntyre who also thought Brock had won the race, only to find out that he hadn't, and didn't realise his mistake until he had. Confusing? You bet! Just imagine how hard McIntyre was kicking himself as Moffat and Brock were handed the trophy!

|

| Check out the marbles off-line. |

Verdict

The first race of 1987 had been an eventful one, a retirement party for the first generation of Group A machinery. Jaguar, BMW, Holden, Ford, Volvo, Nissan, Rover, Alfa Romeo, Toyota... the WTCC was coming up, and once it came we would never see such a variety of badges on the track again. Wellington that January day marked the end of the good old days of Group A. There were great cars and some great drives still to come, but this was perhaps the last time we'd see the ruleset actually function as it was meant to.

And the Mobil Holden Dealer Team? The slam-dunk 1-2 finish was a microcosm of the organisation under Peter Brock's leadership, their excellence in driving and flawless pitwork offset by a single damning fact – they were driving VK-model Commodores, not the newer VL. The VL Commodore SS Group A really should've been on track for Bathurst 1986, and that it wasn't said a lot about Brock's abilities as a manager and product planner. No wonder Holden were losing patience and beginning a dalliance with Tom Walkinshaw: he missed a deadline as crucial as Bathurst, for the second year in a row, despite the free donor cars and generous parts subsidies that came with his status as Holden's official factory team.

So wouldn't you know it, as January became February, that's exactly what he was about to lose...

No comments:

Post a Comment